They are among the estimated 1.4 million people who left the US for medical treatment last year.

For as long as she could remember, Tatum Hosea made the same birthday wish: “I just wanted to be skinny,” she said.

She tried a series of workout plans and diets, developing bulimia in a bid to achieve her goal. Still, the thinness Hosea desired eluded her, and her weight ultimately crept up to more than 300 pounds. She decided last year that a medical intervention would be the only way to win her lifelong weight loss battle. Friends and family members had tried bariatric surgery, and she decided to look into the procedure as well.

“I definitely needed help,” Hosea said. “I would never be satisfied after eating. I would just binge all day long.”

So the stay-at-home mom from Salt Lake City attended a seminar on weight loss surgery presented by a local doctor. When Hosea contacted her insurance company, however, she discovered that bariatric surgery wasn’t covered. Since weight loss surgery without coverage can cost more than $20,000 in the United States, Hosea decided to make other arrangements. She would have the surgery; she would simply travel to Mexico to do so.

The 28-year-old is part of a growing trend. Although the exact number of Americans who leave the US for health care is unknown, medical tourism is rising in popularity. The research paper “Medical Tourists: Incoming and Outgoing,” published in the American Journal of Medicine in July, estimated that 1.4 million Americans sought health care in foreign countries in 2017 and predicted that number will rise by 25 percent this year. Along with dentistry, cosmetic surgery, cardiac treatment, and IVF, weight loss surgery is one of the top reasons Americans partake in medical tourism. And Mexico is one of the most popular destinations for such trips.

Medical tourism is on the rise for complex reasons. It’s not a phenomenon sparked solely by the uninsured, since many insured Americans cross the border for health care too. Like Hosea, they may be underinsured, leaving them with few options for costly medical treatment other than traveling abroad. This move can shave off as much as 40 to 80 percent from the cost of care.

Many medical professionals, though, have concerns about the risks of medical tourism. Hospitals outside the US may have different standards of care, and patients who develop complications risk having to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars for corrective procedures upon returning to the States.

Some physicians find it objectionable that obese patients end up in this predicament at all. Insurance companies and employers, they say, should cover surgery for obese patients just as they cover cardiac surgery for patients with heart disease or lung cancer treatment for smokers. Denying overweight people a wide range of medical options blames them for their health problems, amounting to a covert form of fat shaming.

Weight loss surgery can be life changing for patients with chronic obesity

Bariatric surgery refers to a variety of medical procedures, including gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, adjustable gastric band, and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. While performed differently, all of these procedures help patients lose weight by limiting how much food the stomach can hold as well as the patient’s absorption of nutrients. Bariatric procedures may also affect hormones related to hunger, leading to reduced appetite and improved satiety after eating.

Hosea opted for the gastric sleeve, a procedure that eliminates approximately 80 percent of the stomach. In the end, the organ resembles a tube-like pouch, making it difficult to overeat. This irreversible surgery may lead to long-term nutritional deficiencies, but Hosea felt comfortable with it because both friends and family had it done without a hitch.

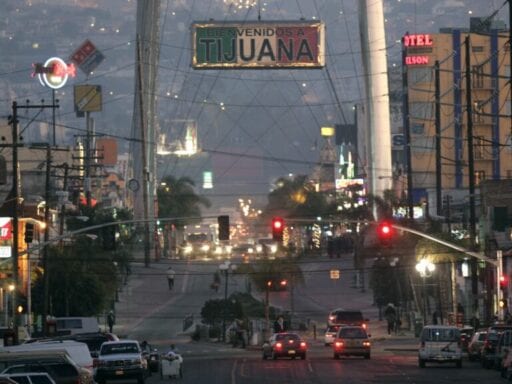

In August 2017, Hosea traveled from her home in Salt Lake City to the Mexico Bariatric Center in Tijuana for the gastric sleeve operation. But she wasn’t alone; her father, who also struggled with his weight, decided to have the surgery as well. Hosea pointed out that she’s Polynesian, an ethnic group that is vulnerable to obesity. Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders are three times more likely to be obese than Asian Americans generally, and 20 percent more likely to be obese than whites.

“My dad was prediabetic,” Hosea said. “I was not, but I hated how I felt. I couldn’t run around after my kids. It was really rough.”

Hosea didn’t set foot in the Mexico Bariatric Center until the day before her surgery, but she and her father had already agreed to walk away if either felt uneasy. Instead, she found the staff, most of whom spoke some English, to be caring and comforting, she said. She recalls the anesthesiologist asking her to count backward from 20, and before she knew it, she was in the recovery room awakening from the procedure.

Hosea estimates that she saved $9,000 by having the operation in Tijuana instead of stateside. An American doctor gave her a quote of roughly $14,000 for the procedure, while she paid just $5,000 for the sleeve gastrectomy in Mexico.

“It was the best decision I ever made,” Hosea said. “I’ll just come out straight and say I have no shame in what I did. I’m glad I did it. Some people are secretive about it. I’m just grateful that it helped me.”

Today, Hosea has lost nearly 90 pounds and about five dress sizes. She said she’s had no complications from having surgery abroad, nor has her father, Jason Porter.

Like Hosea, Porter chose to have weight loss surgery in Mexico because his medical insurance didn’t cover the procedure. He was approaching 300 pounds before the operation and weighs about 220 now, he said. At 6-foot-2, that still makes him about 25 pounds overweight, but he’s no longer in the obese category. He said shedding pounds has enabled him to participate in athletic activities, like golf, that he used to enjoy but found too difficult to play after putting on weight. The 53-year-old also had health problems, such as high cholesterol, hypertension, and borderline diabetes. These conditions have all improved or reversed since his gastric sleeve operation, he said.

The surgery has also changed Porter’s eating habits. Junk food is out, and overeating now causes physical discomfort. Because his stomach is now shaped roughly like a banana, he takes care to eat nutrient-dense foods like fruits, vegetables, and proteins to meet his dietary needs.

Despite these transformative results, Porter said he’s subjected to shaming from people who believe his operation was the easy way out of morbid obesity.

“When we talk about gastric sleeve surgery, people think, ‘So that’s how you did it. You all cheated. You didn’t lose weight on your own,’” Porter said. “I don’t care if I cheated. It’s about the outcome, not about the process.”

Although he had some apprehension about having his procedure in Mexico, Porter was mostly comfortable with the decision because he speaks Spanish, having lived in Latin America as a child. Speaking the language fluently meant that he could communicate with the medical staff and overhear if they discussed anything untoward. Porter said he also felt at ease at the medical center because he knew that health care facilities in countries like Mexico might look different from similar facilities in the US.

“Some Americans would see what looks like a small apartment complex in a not-upscale neighborhood,” he said. “That would have been alarming to a lot of people.”

But having been in such facilities as a child, Porter felt comfortable. The sight of a smiling American leaving the medical center just as he and his daughter arrived also put him at ease.

Still, “I was prepared to leave if anything wasn’t good,” he said. “I was prepared to just take off.”

Guidelines for health care are being standardized at medical facilities worldwide

Following one’s instincts while in a foreign country for medical treatment can be lifesaving, according to Josef Woodman, the CEO of Patients Beyond Borders, which provides information to consumers about international health care travel. He encourages patients considering going abroad for health care to thoroughly research the medical facility they plan to visit for treatment. He says Americans undergoing surgery abroad would be wise to seek care in a multidisciplinary hospital or in a medical center that’s close to one, because such facilities are equipped with emergency rooms, intensive care units, and infectious disease teams.

“If something goes wrong with the patient, they have immediate access to care,” he said.

The Joint Commission International works to improve safety at health care facilities domestically and globally. The leading standards-setting and accrediting body for medical treatment in the US, the commission has assessed more than 20,000 health care organizations. Increasingly, it has given accreditation to international medical facilities, helping to standardize health care across borders. Accreditation ensures facilities are up to date, physicians are board-certified, plans for follow-up care are in place, risks of traveling after surgery are outlined, and more.

According to the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, a rise in medical tourism prompted the US-based JCI to establish guidelines for international facilities. The society last reviewed its data on medical tourism in 2015, noting that the number of JCI-accredited hospitals worldwide had increased by almost 1,000 percent over a five-year period. More than 250 facilities in 36 countries now have the accreditation, up from 27 hospitals in 2004.

In light of medical tourism’s rising popularity, groups such as the International Society for Quality in Health Care and the International Organization for Standardization have also stepped up efforts to implement guidelines for medical facilities globally.

Woodman has traveled internationally for medical care himself and says that more Americans are doing so because insurance coverage in the US is lacking. Patients who need bariatric surgery may be turned down because they’re obese but not quite obese enough. And people who do qualify for medical intervention may not have enough money to pay for the cost of surgery, which frequently includes hidden or unexpected fees.

“With all of the copays, deductibles, gotchas — ‘Yeah, we don’t cover the anesthesiologist’ — you’re paying much more than quoted,” he said. “You can be insured but underinsured, unless you have a Cadillac-level insurance plan.”

An estimated 28 percent of Americans, or 41 million, are underinsured. In some cases, insurance companies do cover weight loss surgery but a patient’s employer has not purchased the “rider” needed for bariatric coverage. Since typical health plans do not include these procedures, employers have to specifically opt in to such coverage.

The high cost of having surgery in the US, even with health insurance, makes bariatric procedures in foreign countries “very, very attractive” for people desperate to have them, Woodman said.

But he cautions the public not to rush into surgery at the first medical center that offers a “good” deal.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13224297/gastricsleevesurgery.jpg) BSIP/UIG Via Getty Images

BSIP/UIG Via Getty Images“Many people shop around for bariatric surgery,” he said. “They’re always looking for the lowest price, but you get what you pay for. That’s why you end up with botched surgeries, going to places with no license, having surgeries conducted in hotel rooms, in … clinics that are not as well-accredited and a little shady. Those are the ones with the low prices, and desperate or gullible people are going to those clinics.”

Woodman also noted that having weight loss surgery outside the US often means forgoing the extensive mental health and nutritional counseling patients receive domestically. Bariatric patients in the States typically work with medical professionals about implementing lifestyle and behavioral changes prior to and following surgery. Before her trip to Tijuana, Hosea had already been in psychotherapy and took it upon herself to research how to maintain weight loss after a bariatric intervention. She said the medical facility she visited for her procedure didn’t provide this information, however.

That’s not the only drawback to having weight loss surgery in Mexico, or any other foreign country. Should complications arise, it can be difficult to access the surgeon again if the patient lives far from the border. Coordinating follow-up care can also be a challenge.

Postsurgical care is important since patients may experience problems, like gastric leaks, after their procedures. As with any surgery, bariatric operations also carry a small risk of death. In the US, the average mortality rate for bariatric surgery is under 0.3 percent, but it can be as high as 2 percent for some patients.

“It’s not getting a filling, having an MRI, IVF, or an orthopedic procedure,” Woodman said. “There’s a lot of opportunity for complications with bariatrics.”

Doctors and patients alike agree — often from firsthand experience.

Medical tourism has a dangerous dark side unknown to many patients

Dr. Hamilton Le, the medical director of Integris Weight Loss Center in Oklahoma City, noticed a disturbing trend last year.

“We had a string of maybe eight patients in a row, every three to four weeks, who just recently had sleeve gastrectomy surgery in Tijuana, Mexico, and they all came from small towns in Oklahoma,” he said. And all of them had surgical complications.

Risks of gastric sleeve surgery include wound infections, a very narrow stomach pouch, as well as the previously mentioned gastric leaks, whereby the stomach contents exit the patient’s abdomen.

“This causes severe pain and infection,” Le said. “If they abscess, they need to have drain surgery or radiology puts a drain in. They need an IV to give them antibiotics and nutrition, which can be very expensive. They may get really sick and need to be in the ICU.”

Le suspects that medical tourism facilitators swayed the patients he’s treated to cross the border for surgery, packaging the trip as a dream vacation.

“They arrange for these people to go have surgery in sunny, beautiful Mexico,” he said. “They show them these beautiful luxury accommodations, and it’s $4,000 for the entire trip — transportation, airport, hotel, surgery. It’s this awesome vacation marketed in small towns.”

The patients targeted either don’t have health insurance or have insurance plans that cover weight loss surgery. And predatory medical tourism facilitators receive kickbacks for each patient they convince to have surgery overseas. Allegedly, LuLaRoe executives profited from referring salespeople to Mexico for bariatric surgery, and a lawsuit has been filed against a school district in Arizona because an administrator ran a medical tourism operation from campus. The administrator, who no longer works for the district, admitted to receiving $250 for each of the 300 patients she successfully referred for weight loss surgery in Mexico. A LuLaRoe executive reportedly made $1,000 for every successful referral.

Le contends that once they get paid, medical tourism facilitators are not interested in the health of patients. Before surgery, these facilitators are typically friendly to their referrals, but should problems for patients arise afterward, the recruiters may become hostile or ignore them altogether.

As it is, international surgery tends to be a whirlwind experience for patients.

“They’ll fly out on a Monday, meet their doctor on Monday afternoon, and be on a plane home Wednesday night or Thursday morning with a handful of instructions, pain medicine, antibiotics, and a note to go see their family doctor afterward,” Le said.

If patients develop complications after surgery, some US doctors may not be willing to see them. Physicians don’t want to be liable for patients with medical problems caused elsewhere, Le said. And insurance companies won’t pay for corrective procedures since they didn’t authorize the initial operation. In the end, a patient can end up paying hundreds of thousands of dollars for revision surgeries.

“But nobody warns you about that while you’re sitting in a waiting room before surgery,” Le said.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13224323/lapbandsurgeryad.jpg) LA Times via Getty Images

LA Times via Getty ImagesJustin Blackburn knows firsthand about the risks of an overseas bariatrics procedure. Eleven years ago, he had lap band surgery in Mexico. During this procedure, an inflatable band wraps around the top portion of the stomach, producing a small pouch above the band. The creation of the small pouch helps to make patients feel fuller quicker, leading them to eat less and lose weight. Although Blackburn’s insurance covered the surgery, he was disqualified from coverage for not being obese enough.

“I didn’t meet the [body mass index],” the 43-year-old recalled. “Mine was probably around 35, and they wanted it at 40 in the United States.”

But Blackburn had struggled with his weight for a decade, repeatedly yo-yo dieting. He knew that his stepmother, Elizabeth Erickson, had already gone to Mexico for bariatric surgery, so he decided to travel there from Arizona. He contacted the office of Dr. Ariel Ortiz, a doctor Erickson highly recommended, though she had not been a patient. Ortiz is well-known because he’s a pioneer of the lap band procedure. Blackburn said the doctor’s staff wasted no time arranging for him to have the operation.

“It took about two weeks from the time I contacted his patient sales rep to when I had my surgery,” Blackburn said.

He remembers expressing that he wanted to lose 60 pounds and being asked in response, “How soon can you get us the cashier’s check or Paypal transfer for $8,500?”

Blackburn said no one on staff inquired about his previous efforts to lose weight or presented him with any alternatives to surgery. (An attorney for Ortiz did not respond to Vox’s request for comment.) He proceeded with the operation, which initially appeared to be a success. During the postsurgical care period, however, Blackburn said he developed complications. Patients who undergo lap band procedures must have the devices periodically adjusted, and since he could not return to Ortiz for these adjustments, Blackburn visited an Arizona nurse named Wendy Hall for these follow-ups, as did his stepmother.

Although Hall had received training from Ortiz, Blackburn said she overtightened the band. He maintains that as a result, he developed acid reflux and esophagitis, a condition that causes painful swallowing, chest pain, and stomach acids to travel back up the esophagus.

“As soon as Wendy Hall started adjusting my lap band and overtightening it, I started having trouble swallowing food,” he said. “I was constantly throwing up.”

But Blackburn said his stepmother paid the ultimate price: Erickson developed severe complications after seeing Hall for an adjustment in 2013.

“Wendy Hall overtightened her lab band so tight that her stomach acids leaked out of her stomach into her heart and lungs, and she died of sepsis,” Blackburn said.

Dying from the result of a medical error isn’t limited to the medical tourism industry. Overall, medical errors are the third leading cause of death in the US, with more than 250,000 Americans killed from such mistakes. But a $100 million class-action lawsuit that Blackburn is part of has drawn particular attention to bariatric-centered medical tourism.

Filed this year by the Arizona firm Gregory Law Group, the suit accuses Ortiz, Hall, other medical professionals, affiliated businesses, and consultants of mischaracterizing the “nature, quality, and safety of bariatric procedures.” The lawsuit notes that Erickson died after developing complications from her surgery and aftercare from Hall, who was not a bariatric nurse but a nurse midwife. In May 2017, the Arizona Board of Nursing revoked Hall’s license.

Le considers it a social justice issue that patients with obesity have so few options for medical treatment that they end up in harm’s way. A member of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, Le wants these patients, many of whom are socioeconomically disadvantaged, to have more access to care.

“We are encouraging insurance companies, national carriers, and employers, telling them that when they don’t cover bariatric surgery, we consider it discrimination,” he said.

Le said that obesity is a chronic medical problem like any other health condition, and patients deserve access to a range of treatment options. Refusing such care because of weight bias increases the odds that patients will fall prey to unscrupulous individuals who behave as if they have their best interests in mind.

Five years after his stepmother’s death, Blackburn continues to grieve her loss. And he continues to have health problems.

“I still have esophagitis,” he said. “When I eat, I still have regurgitation problems, and sleeping is an issue.”

But in other ways, his health has improved after losing 130 pounds.

“My weight’s great, and all the other problems related to it, I don’t really have,” said Blackburn, who now lives in Bozeman, Montana. “Before I had surgery, I started having knee and back problems. I didn’t like to be active, but now I live basically at a ski resort. I can hike. I can ski. I can do all these things where I feel like a 30-year-old instead of an 80-year-old. I don’t have high blood pressure, diabetes, or high cholesterol.”

Being able to live life to the fullest is the primary reason Tatum Hosea signed up for bariatric surgery as well. She’s still maintaining her weight loss and taking care not to fall into the unhealthy patterns that ensnared her before her gastric sleeve operation.

“I just wanted to be there for my kids,” she said. “I wanted to be healthy and live a long life. To do everything I’ve always wanted to do.”

Want more stories from The Goods by Vox? Sign up for our newsletter here.

Author: Nadra Nittle