With Justice Kennedy off the Supreme Court, both gay rights plaintiffs and death row inmates face a bleak future.

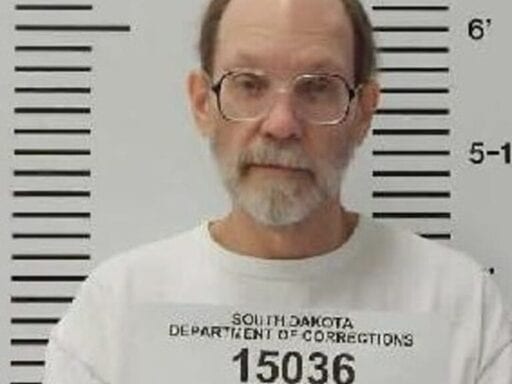

Twenty-seven years ago, Charles Rhines committed a terrible crime. In 1992, a man caught him burglarizing a South Dakota doughnut shop, and Rhines stabbed him to death. He later confessed to the murder and was sentenced to death — and he is scheduled to be executed by South Dakota authorities on Monday afternoon.

As horrific as his crime was, the circumstances surrounding Rhines’s sentencing are troubling. There is evidence — including multiple statements by the jurors who sentenced him to death — indicating that he was not given a death sentence solely because of his crime. Rather, it is likely that Rhines was sentenced to die because he is gay.

During Rhines’s trial, while jurors were deliberating whether to give Rhines a life sentence or death, the jury sent the judge several questions that seemed designed to probe whether Rhines would have the opportunity to have sex with men while he was incarcerated. According to Rhines’s lawyers, the jurors asked “whether his jailers would allow him to ‘mix with the general inmate population,’ ‘create a group of followers or admirers,’ ‘discuss, describe or brag about his crime to other inmates, especially new and or young men jailed for lesser crimes …’ ‘marry or have conjugal visits,’ or ‘be jailed alone or …. have a cellmate.’”

After the trial, several members of the jury came forward and admitted that Rhines’s sexual orientation played a significant role in their deliberations. One said that the jury knew that “he was a homosexual and thought that he shouldn’t be able to spend his life with men in prison.” Another recalled a fellow juror’s statement that “if he’s gay, we’d be sending him where he wants to go if we voted for” life imprisonment. A third juror recalled “lots of discussion of homosexuality. There was a lot of disgust.”

There is no question that Rhines’s crime was terrible. So it’s entirely possible that, were he given a new sentencing hearing, he would ultimately be resentenced to death by a jury that didn’t hold anti-gay views. But the evidence suggests that Rhines’s jury was motivated by a combination of anti-gay animus and an apparent belief that a men’s prison would be a kind of sexual prowling grounds for a gay inmate.

Rhines’s fate, moreover, was likely sealed last April, when the Supreme Court turned aside a petition raising the evidence that jurors were motivated by Rhines’s sexual orientation. That decision not to hear the case came a little less than a year after Justice Anthony Kennedy, who often voted with his liberal colleagues in gay rights cases and in death penalty decisions, left the Court to be replaced by the conservative stalwart Brett Kavanaugh.

So, while Rhines is not an especially sympathetic individual, his execution likely represents a new age in American law. Parties alleging that the Constitution restricts anti-gay animus can no longer expect to find relief in court, and death row inmates will have far less recourse to the Constitution.

The death penalty is reserved for the most severe offenses — for now

“When the law punishes by death,” Kennedy wrote for the Court in Kennedy v. Louisiana (2008), “it risks its own sudden descent into brutality, transgressing the constitutional commitment to decency and restraint.” For this reason, Kennedy wrote in an earlier opinion, “capital punishment must be limited to those offenders who commit ‘a narrow category of the most serious crimes’ and whose extreme culpability makes them ‘the most deserving of execution.’”

It is far from clear that these warnings against the overzealous use of the death penalty will survive Kennedy’s retirement. Last April, in one of the Supreme Court’s first major death penalty decisions since Kennedy stepped down, the Court’s new majority seemed to walk back decades of decisions interpreting the Eighth Amendment’s ban on “cruel and unusual punishments.”

“Death was ‘the standard penalty for all serious crimes’ at the time of the founding,” Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote for that new majority in Bucklew v. Precythe (2019). Bucklew, moreover, strongly implies that the proper question that courts should ask in an Eighth Amendment case is whether a particular punishment would have been considered cruel and unusual “by the time of the founding.” Bucklew, in other words, suggests that the Court may be prepared to expand the universe of crimes that can result in a death sentence.

At least for the moment, however, the Court has not overruled cases like Kennedy, which reserves executions to the most heinous crimes. Current law, moreover, requires trial courts to conduct a two-stage process whenever a defendant may be killed by the state.

In the first stage, often referred to as the “guilt” phase of the trial, the jury determines whether the defendant committed the crime they are accused of committing. Rhines was convicted of murder during this phase of his trial, and there’s little reason to doubt the soundness of that conviction, given his confession.

The second stage, often referred to as the “penalty” phase, is when the jury decides whether a death sentence is appropriate. This phase, as Justice Potter Stewart explained in the 1976 case endorsing this two-stage framework, focuses “the jury’s attention on the particularized nature of the crime and the particularized characteristics of the individual defendant.” Prosecutors typically present evidence that the individual is particularly depraved or the crime was particularly heinous, while defense attorneys will point to factors that mitigate the seriousness of the crime or suggest that the defendant deserves mercy.

There are very serious doubts about whether this process eliminates arbitrariness and prejudice from death sentences. Data suggest that people of color are more likely to be executed than white offenders, and that executions are more common when the victim is white. (Rhines and his victim are both white.)

Yet, as a matter of raw numbers, existing safeguards do tend to restrict the death penalty to just a handful of individuals. In 2017, there were more than 17,000 homicide crimes in the United States. Yet only 39 people were sentenced to die.

Existing law, in other words, recognizes that death sentences should be rare and should be reserved for the very worst offenders. Perhaps a jury could have concluded that Rhines’s crime cleared this high bar. But that inquiry should have focused on the nature of Rhines’s crime and any indications that he is a particularly remorseless offender. It should not have focused on Rhines’ sexual orientation.

Anthony Kennedy’s unfinished gay rights revolution

If the Supreme Court, with its current very conservative majority, had taken Rhines’s case, they could have used it as a vehicle to roll back existing rights for victims of anti-LGBTQ discrimination. At the very least, the Court’s Republican majority would not have had much trouble ruling against Rhines because existing doctrine does not shield against all forms of anti-LGBTQ discrimination by the government.

Though Justice Kennedy was a conservative Reagan appointee who typically voted with his Republican colleagues, his views on gay rights were fairly moderate. Over the course of nearly two decades, Kennedy authored a series of decisions striking down some forms of government discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. After Justice Sandra Day O’Connor left the Court in 2006, these decisions typically split the Court 5-4, with Kennedy joined by his four liberal colleagues.

Yet, while Kennedy frequently supported gay rights, he did so very slowly, typically handing fairly narrow victories to victims of anti-gay discrimination, then letting these victims wait years for the next incremental step towards equality. (Notably, Kennedy’s very short record on transgender rights suggests that he was far less sympathetic to plaintiffs alleging discrimination on the basis of gender identity than he was to plaintiffs in sexual orientation cases.)

His first major gay rights decision in Romer v. Evans (1996), for example, merely held that the government cannot enact laws solely because of its “desire to harm a politically unpopular group.” The Court didn’t hold that adults cannot be prosecuted for consensual sexual activity, including same-sex activity, until seven years later in Lawrence v. Texas (2003).

By the time Kennedy got around to marriage equality, he doled out the right to marry partners of the same sex out in two stages. Kennedy’s first marriage equality decision, in United States v. Windsor (2013), only held that the federal government could not deny equal rights to couples who legally married under the marriage laws in their state. Same-sex couples did not gain full marriage rights in all 50 states until two years later in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015).

And, even then, Kennedy was stingy. Broadly speaking, there are two ways Kennedy could have reached his marriage equality decision in Obergefell. He could have written a broad decision holding that any governmental discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is constitutionally dubious. Or he could have written a narrow decision holding that the Constitution protects a fundamental right to marry, and that specific right cannot be denied to same-sex couples.

Though Obergefell hinted that a broad decision would come later, Kennedy never held that discrimination based on sexual orientation is inherently dubious. Instead, he opted for the narrower option in Obergefell — and then he left the Court three years later. The result is that Kennedy’s gay rights revolution is a revolution interrupted. Kennedy never got around to a decision holding that the Constitution casts a skeptical eye on all discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.

With Kennedy gone, that decision may not come for a very long time.

Author: Ian Millhiser

Read More