The scientific faces of Trump’s failed coronavirus response wasted no time speaking out.

It didn’t take long for the two scientific faces of former President Donald Trump’s failed coronavirus response to speak out about how dysfunctional efforts to curb the pandemic really were under the 45th president.

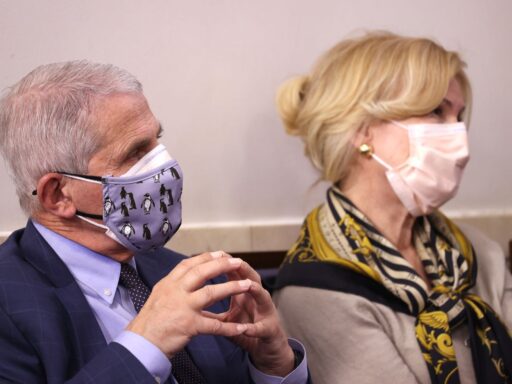

On the first weekend following Trump’s departure from the White House, Dr. Anthony Fauci and Dr. Deborah Birx — both members of the Trump White House coronavirus task force coordinated by Birx — did interviews with national media outlets in which they described a culture in the Trump White House that discounted scientific expertise and put a premium on the type of denialism that resulted in Trump continuing to hold packed political rallies even as coronavirus deaths and cases soared in the fall.

“We would say things like: ‘This is an outbreak. Infectious diseases run their own course unless one does something to intervene.’ And then he would get up and start talking about, ‘It’s going to go away, it’s magical, it’s going to disappear,’” Fauci told the New York Times.

Birx made similar comments to CBS during an interview with Face the Nation host Margaret Brennan, saying “there were people [in the White House] who definitely believed that this was a hoax,” and adding that Trump had a penchant for listening to people who told him what he wanted to hear, even if that information had no scientific basis.

“I saw the president presenting graphs that I never made,” she said. “So I know that someone — someone out there, or someone inside — was creating a parallel set of data and graphics that were shown to the president. I don’t know to this day who, but I know what I sent up, and I know what was in his hands was different than that.”

“I saw the president presenting graphs that I never made. So I know that someone … was creating a parallel set of data and graphics that were shown to the president. I don’t know to this day who.” — Dr. Birx pic.twitter.com/ql811iB8WG

— Aaron Rupar (@atrupar) January 24, 2021

Fauci corroborated that point, telling the Times that in the early days of the pandemic, he was “really concerned” to observe that Trump “was getting input from people who were calling him up, I don’t know who, people he knew from business, saying, ‘Hey, I heard about this drug, isn’t it great?’ or, ‘Boy, this convalescent plasma is really phenomenal.’”

“He would take just as seriously their opinion — based on no data, just anecdote — that something might really be important,” added Fauci. “It wasn’t just hydroxychloroquine, it was a variety of alternative-medicine-type approaches. It was always, ‘A guy called me up, a friend of mine from blah, blah, blah.’ That’s when my anxiety started to escalate.”

Birx’s tell-all represented an effort to rehabilitate her damaged reputation

Birx emerged from the Trump era with her reputation more in tatters than Fauci. While both of them went to pains to avoid contradicting the president in public, Birx’s tendency to effusively praise Trump, even as he touted unproven miracle cures and downplayed the severity of a pandemic that killed 400,000 Americans before he left office, made it seem that she was putting politics first.

“[Trump is] so attentive to the scientific literature & the details & the data. I think his ability to analyze & integrate data that comes out of his long history in business has really been a real benefit” — this is shocking, hackish stuff from Dr. Birx. pic.twitter.com/c2phsRYaJs

— Aaron Rupar (@atrupar) March 27, 2020

Fauci did not share this tendency. He refused to disparage Trump, even given the chance, but did often contradict the former president publicly.

Unlike Fauci — who now serves as a medical adviser to President Joe Biden in addition to his role as director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases — Birx was not asked to join the Biden administration. This made her interview with CBS seem, in part, an effort to rehabilitate her image ahead of her forthcoming retirement from the federal government.

Birx became emotional when talking about her legacy and how it may end up being tarnished by her time coordinating the Trump White House’s coronavirus task force. She tried to push back on the perception that she at times was more concerned about staying in Trump’s good graces — something Fauci didn’t seem to care about — than she was about leveling with the American people.

Asked about an infamous incident during a press conference in which Trump suggested to her that disinfectant injections or sunlight treatments could be miracle cures for the coronavirus, Birx tried to minimize her role.

“I didn’t even know what to do in that moment,” she said, adding later: “People then want to define you by the moment.”

WATCH: Birx reacts to claims that she became an “apologist” for Trump and *that* moment where the former president suggested using disinfectant as a potential treatment for #COVID19

“I wasn’t prepared for that. I didn’t even know what to do in that moment.” pic.twitter.com/2ddCblGllH

— Face The Nation (@FaceTheNation) January 24, 2021

However, that was far from the only time Birx failed to correct bad information Trump was giving the public. There were numerous occasions in which she appeared to go out of her way to run interference for poor decisions Trump made, ranging from defending his refusal to wear a mask to cajoling the CDC to exclude presumed positive cases from the coronavirus death count. She told CBS she constantly considered resigning, but said she did not because she thought she could do more good from inside the government. Finally, she came to the conclusion “right before the election” that “I wasn’t getting anywhere.”

Birx claimed during the interview that Trump “appreciated the gravity” of the pandemic in March and April, only to lose focus as “the country began to open” and Election Day neared. While reporting from journalist Bob Woodward did reveal in September that Trump quickly came to the realization that the coronavirus posed a serious threat, what Birx’s claim overlooks, however, is that Trump did not share these private beliefs with the American people.

Instead, he spent the earliest months of the pandemic saying the coronavirus would go away on its own “like a miracle” and dismissing efforts by Democrats to take it more seriously as “a hoax.” Fauci’s interview with the New York Times shed light on how Birx’s account revises history.

Fauci’s interview highlights Trump’s fundamental unfitness

While Birx made it seem as though Trump’s coronavirus response started strong, Fauci’s interview with the Times paints a picture of a president who was incapable of competently responding to a pandemic — and who engaged in magical thinking from the start.

“I would try to express the gravity of the situation, and the response of the president was always leaning toward, ‘Well, it’s not that bad, right?’ And I would say, ‘Yes, it is that bad,’” Fauci said. “It was almost a reflex response, trying to coax you to minimize it. Not saying, ‘I want you to minimize it,’ but, ‘Oh, really, was it that bad?’”

Those comments echo statements Fauci made last Thursday during his first public comments as a Biden adviser, when he characterized Trump’s departure from office as a breath of fresh air.

“One of the new things in this administration is if you don’t know the answer, don’t guess. Just say you don’t know the answer,” Fauci said during last Thursday’s press briefing, adding at another point that Trump’s touting of unproven and potentially dangerous “miracle cures” for the coronavirus was particularly “uncomfortable” for him, “Because they were not based in scientific fact.”

REPORTER: You’ve joked a couple times about the difference between the Trump and Biden administrations. Do you feel less constrained?

FAUCI: You said I was joking about it. I was very serious. I wasn’t joking. pic.twitter.com/nyH4ow1zVj

— Aaron Rupar (@atrupar) January 21, 2021

While Fauci tried to avoid directly rebuking Trump publicly, he did contradict his false claims about Covid-19 being as deadly as the flu and tried to correct the record when Trump would promote unproven treatments as possible cures for the coronavirus. He told the New York Times that even before Trump mused about firing him at one of his campaign rallies, he received death threats — and in one case, a letter containing powder.

“One day I got a letter in the mail, I opened it up and a puff of powder came all over my face and my chest,” he said.

“That was very, very disturbing to me and my wife because it was in my office,” he continued, adding that, thankfully, the substance turned out to be “a benign nothing.”

Fauci at one point expressed empathy for Birx because she had to deal on a daily basis with Scott Atlas — a neuroradiologist with no prior infectious disease expertise Trump brought into the White House as a coronavirus adviser. Atlas was a proponent of the discredited idea that the federal government should let the coronavirus infect as many people as possible.

“I tried to approach [Atlas] and say, ‘Let’s sit down and talk because we obviously have some differences,’” Fauci told the Times. “His attitude was that he intensively reviews the literature, we may have differences, but he thinks he’s correct. I thought, ‘OK, fine, I’m not going to invest a lot of time trying to convert this person,’ and I just went my own way. But Debbie Birx had to live with this person in the White House every day, so it was much more of a painful situation for her.”

Atlas’s unwillingness to hear anything he didn’t want to hear was a characteristic he shared with Trump, who did his best to ignore his own CDC’s advice about gatherings, holding superspreader rallies during his failed reelection campaign, even as scientific experts warned that the US was heading into a winter in which cases and deaths would spike. Trump ended up in the hospital in early October after he contracted the virus, but even that experience didn’t chasten him.

As Fauci told the Times:

When [Trump] was in Walter Reed [hospital] and he was getting monoclonal antibodies, he said, “Tony, this really just made a big difference. I feel much, much better. This is really good stuff.” I didn’t want to burst his bubble, but I said, “Well, no, this is an N equals 1. You may have been starting to feel better anyway.” [In scientific literature, an experiment with just one subject is described as “n = 1.”] And he said, “Oh, no, no no, absolutely not. This stuff is really good. It just completely turned me around.” So I figured the better part of valor would be not to argue with him.

None of this is surprising — but it’s still notable

What Birx and Fauci said during their interviews isn’t necessarily surprising. We’ve long understood that the Trump White House’s coronavirus response was a disaster, especially when compared with countries like Australia and Japan that have done a much better job limiting infections and deaths. We’ve known that Trump has a tendency to engage in wishful thinking and has an aversion to scientific reasoning.

But what Birx and Fauci’s willingness to speak out in the immediate aftermath of Trump’s departure from office does illustrate is just how bad things were under the previous administration. It now falls upon the Biden administration to try to clean up the mess left behind after a year of politically motivated, short-term thinking, in which public health experts like Fauci and Birx had to struggle on a daily basis with questions about whether it was worth it for them to keep showing up at work.

Author: Aaron Rupar

Read More