The inside story of how the beauty company and its controversial founder changed an industry forever.

There’s a big hunk of human skin in the freezer. It’s in a plastic-wrapped package and labeled as a “full thickness” sample from a 67-year-old woman. It takes a flat rectangular form that looks like a slab of bacon, about two inches thick. It’s from the woman’s back; she apparently died from cancer.

This skin will be doused in hyaluronic acid or perhaps slathered with vitamin C, two of the most popular and effective ingredients in serums, moisturizers, and all matter of face potions today. The skin care company Deciem spent hundreds of dollars and jumped through many mandated regulatory hoops to obtain this sample, which was donated to a company called Science Care. Beauty companies and labs often use samples like this one, or sometimes synthetic skin or lab-grown skin cells, to test the absorption of their products.

This particular sample is housed in a light-filled laboratory at the new Deciem headquarters in Toronto. Sun streams in and highlights the vials, technical instruments, and powdered jars of chemicals that are scattered around.

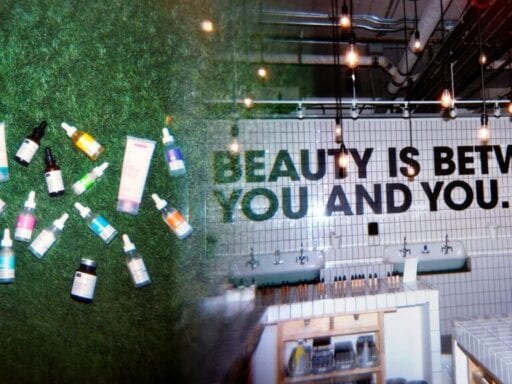

In the seven years since its founding, Deciem has totally changed how we think about and buy skin care. Thanks mostly to its biggest brand, the Ordinary, it’s allowed a new generation of consumers to understand ingredients, and perhaps more radically, offered them in ridiculously cheap formulations. It’s championed transparency in an industry that wants you to think expensive products are better — an industry where inviting me, a reporter, to poke around in the skin samples and see how formulas are made is unheard of.

Last year, Deciem was reportedly on track to do $330 million in sales. (To put that into perspective, buzzy mattress company Casper sold a little over $350 million in 2018.) Estée Lauder, the enormous and enormously influential conglomerate that owns brands like Clinique and MAC, took a minority investment in the company in 2017, a rarity for the beauty giant and a sign of extreme confidence. The brand was ripe for a global explosion.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19780649/SP_2.jpg)

Back in December, I came to Deciem HQ for some closure on almost four years of reporting. I’ve been covering the company since 2016, when it started to gain momentum with shoppers. The story I’ve sought to tell and follow has ostensibly been about the business and the culture of beauty. But somewhere down the line, Deciem’s charismatic and complicated founder Brandon Truaxe hijacked his own company’s narrative.

As Deciem’s profile grew, Brandon’s increasingly erratic and bizarre behavior became media fodder as company drama played out on Deciem’s heavily-followed Instagram account. It was also playing out in my inbox, where Brandon bombarded me with emails, sending his own ramblings and also copying me on official business conducted with his lawyers and Estée Lauder.

I was one of the first to report on the brand, and had already been in regular communication with not only its founder but many others at Deciem. I soon found myself a minor player in the company’s story, being tagged in Brandon’s posts and showing up in screenshots of emails he’d sent, an uncomfortable and confusing position for a journalist to be in. I was also worried about him, and had reason to be.

He died at the age of 40 after falling from the balcony of his Toronto condo in January 2019, a few months after being ousted from his company. It was a story I broke here at Vox. A year later, it’s surreal being at the Deciem office, this place that Brandon dreamed of, with the company thriving and its impact felt across the entire $532 billion beauty industry.

Brandon, born Ali Roshan, grew up in Iran and moved to Canada in the 1990s when he was in his early twenties. He was trained as a computer programmer, and at the start of his career, did work for a beauty corporation. While there, he became aware of and annoyed by the high prices the company was charging for products made from inexpensive ingredients. He also saw an opportunity and launched his own luxury line called Euoko in 2006. He charged over $500 for some of the products.

When Euoko failed, Brandon teamed up with new partners on a more affordable skin care brand called Indeed Labs. He left in 2012 after a falling out with the team, the details of which have never been aired publicly. I used to ask him about these former business ventures, but he was always vague; people who worked with him during this period won’t go on the record to talk about those years. There are legal documents that exist around some of Euoko’s dealings and a press release stating that he sold it for $72 million. It doesn’t say to whom.

But then came Deciem.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19780651/SP_3.jpg)

After leaving Indeed Labs, Brandon’s non-compete prohibited him from formulating facial skin care products for two years. He got around it by launching a brand called Inhibitif whose products prevented hair regrowth, a supplement drink brand called Fountain, and an anti-aging hand care brand called Hand Chemistry, all under the umbrella of a company called Deciem (tagline: “The Abnormal Beauty Company”). His plan was always to incubate and launch multiple brands contemporaneously, a difficult and unusual tactic in beauty, where research and development can take years.

NIOD, the company’s marquee skin care brand, came to market right after his non-compete expired, but it was the launch of the Ordinary in 2016 that changed the game. This is when I and thousands of other people who lurked on skin care forums and kept up on industry news became aware of the company. My cringey-in-hindsight headline from September 2016, a month after the launch, was: “Deciem Might Be the Most Thrilling Thing To Happen to Skincare in a Long Time.” It managed to be hyperbolic while also hedging my bets. And I was right.

Deciem quoted my headline on its social media accounts and in the press section of its company site; I was suddenly on Brandon’s radar. Mine was one of the earliest stories about the brand, and soon others appeared in magazines and on websites, propelling the Ordinary forward. A key takeaway in these pieces was just how ridiculously inexpensive the line was; consumers ate it up. Estée Lauder came calling not long afterward and made a landmark investment in Deciem.

Before the Ordinary, known simply as “TO” by its fans, the cheapest skin care formulas came from drugstore brands like Neutrogena and L’Oréal. Marketing focused on flowery descriptions that suggested vague benefits. If ingredients were mentioned, they were usually proprietary blends with made-up names like Pro-Xylane. Price tags regularly pushed past $20, even for mass-market formulas. In the upper echelons of the skin care market, brands like La Mer and SK-II charged hundreds of dollars for their products, paying celebrities like Cate Blanchett millions to endorse their lines.

The Ordinary’s bestseller, a niacinamide and zinc blend, costs $5.90. In fact, the majority of the brand’s products check out at under $10. They contain only a few active ingredients, and tend to be ones that have been used and understood for years, like vitamin C (a brightening antioxidant), retinol (a fine-line fighter), and hyaluronic acid (a hydrator). They’re building blocks. There are no vague promises on the bottles, no fancy masking fragrances, no celebrity spokespeople, no glossy ads. The product descriptions online read like a pharmacology textbook: “A high 10% concentration of this vitamin is supported in the formula by zinc salt of pyrrolidone carboxylic acid to balance visible aspects of sebum activity.” Translation: It will make you less greasy. Skin care had never been sold like this, or for such a low price.

Deciem never imagined the brand would take off the way it did, now driving almost 80% of its business. In fact, Brandon saw the launch as a way to snub his nose at the rest of the skin care industry. At the time, NIOD, whose most expensive product costs $90, was Deciem’s “crown jewel, where the innovation is,” according to Nicola Kilner, Deciem’s current CEO. It uses compounds and molecules that aren’t common; formulas are improved upon frequently, with different versions listed online like software updates.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19780661/SP_4.jpg)

NIOD was being sold next to national brands that marketed expensive formulas containing basic ingredients like vitamin C as innovative. In other words, workhorses dressed up as show horses.

“The Ordinary only launched to make a marketing point,” says Nicola. “We never thought it would be a commercial brand.”

Price markups are high in beauty, often hundreds of percentage points higher than what the products cost to produce, but no one talks about it. Ingredient suppliers make brands sign NDAs, and while brands are required to list their ingredients on labels, many don’t share concentrations. Unlike the vast majority of beauty companies, Deciem is vertically integrated and owns its factory. It formulates, produces, and packages its products in-house. This allows it to bring products to market more quickly, keep formulas private, and cut down on cost. “The idea was, let’s start to communicate these trusted ingredients because they’re so affordable,” says Nicola.

The Ordinary hit at a time when the skin care discourse was about to explode into the mainstream. Online forums like Reddit’s r/SkincareAddiction and r/AsianBeauty (they have almost 2 million followers combined) were already deeply into Korean skin care, which gained traction in the US around 2014. K-beauty, as it’s called, advocates a 10-step routine with product categories like essences and ampoules, which had never existed in Western routines. People in these online communities dug into ingredient claims and experimented with regimens.

“I wanted to stock the Ordinary from the minute I heard the brand story, but we took some time to test the products before launching because it really did sound too good to be true,” says Alexia Inge, a co-founder of Cult Beauty, the British e-commerce site known for stocking beauty brands right as they’re becoming hot.

She already carried NIOD, and was beginning to see a change in how her customers approached buying skin care. “A decade ago Cult Beauty’s customers were asking, ‘What’s the best moisturizer for dry skin?’” she says. “Now they want to know the size of the hyaluronic acid molecules.” The Ordinary played perfectly into this dynamic, at a price point that made experimentation financially painless.

Personalization of skin care was becoming widespread, with people no longer wanting to settle for one-size-fits-all creams. And after the 2016 election and the chaos of Brexit, choosing the right formulas, whether for efficacy or for the ritual itself, became associated with self-care. Jia Tolentino wrote about this phenomenon for the New Yorker: “I bought it, along with a bunch of other stuff, unsure if I was buying skin care or a psychological safety blanket, or how much of a difference between the two there really is.”

As the popularity of forums like Reddit, the early K-beauty bloggers like Skin&Tonics and Fifty Shades of Snail, and the viral Google skin care doc from The Strategist’s Rio Viera-Newton have proven, peer-to-peer recommendations are now critical for building brand trust in the beauty world. The internet has completely democratized how we buy so many things, and skin care is no exception. Magazines and celebrities are no longer the arbiters of knowledge — your friendly neighborhood obsessives are.

One of the most influential spaces for Deciem has been the Facebook group the Ordinary & Deciem Chat Room, which popped up entirely independent of the company. Not to sound like a broken record, but this too is not a thing that happens in beauty. Sure, there are tons of general beauty forums; however, there are not many brand-specific ones, and certainly not at such a scale.

The group now boasts over 129,000 followers and has inspired several copycats. Its founder, Jo Ingram, is a 45-year-old British woman who has lived in Spain for the past 17 years. Back in January 2017, like so many others, she was interested in putting together a skin care routine and stumbled across a post on Facebook that mentioned the Ordinary.

”Once you go to the website and see all the products and prices, you want part of it,” Jo told me over the phone. “It has the most amazing effect on you, and all you do is talk about the Ordinary.”

Jo found Deciem’s ingredients and product descriptions confusing, so she reached out to the company to ask for help. While waiting for a response, she started a Facebook group for her friends to have conversations about the products. It gained followers outside of Jo’s circle through word-of-mouth. Eventually, Deciem got wind that it existed and Brandon himself did a Q&A with fans on the page. It was supposed to be a two-hour live event, but he spent a full day answering every single comment and question. The thread now has 1,200 comments.

Jo describes the Chat Room as her full-time job. It has an accompanying Instagram account and a website, where she offers sample regimens based on skin concerns and publishes posts on the basics of the brand. She earns money through affiliate commissions and from retailers who advertise on Instagram and in the group. She does not, however, accept money directly from Deciem; it’s important to her that the group remains financially independent from the brand so that it can continue to publish frank member reviews.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19780668/SP_5B.jpg)

She describes several types of people who engage on her platforms. There are the superfans, who “keep all their empty bottles and boxes,” and post pictures of them on Instagram. There are those who really dig into the formulas. Then there are those who want something that works, but don’t care about molecule sizes or concentrations. These people, she says, “buy because it’s inexpensive and want to be told what to use while they’re still learning.” A few weeks after they make an initial purchase, she’ll see these newbies helping others.

She sometimes plans her vacations around where the Facebook group’s moderators are located, so she can meet up with them IRL. “I’ve seen many people start up their own groups, pages, websites, and Instagram accounts. Some of the moderators were already bloggers and now have YouTube channels and podcasts,” she says. “It’s truly amazing watching the mods and also the members of the group grow, all from the interest in skin care, which goes back to Deciem.”

She acknowledges that not every product is for everyone, and people do excoriate Deciem products that don’t work for them. (The niacinamide product, despite being the brand’s bestseller, can be particularly divisive.) She’s proud of what she calls the group’s “honest reviews.” Still, she says, “I don’t know any other skin care brand that has this effect on people.”

People who knew Brandon describe him as a genius. He was frenetic, never standing still, talking fast, always expressive. (Watch this for a perfect encapsulation of his mannerisms.) He was lanky and favored flashy T-shirts from designers like Diesel. Over the years, his face became more sculpted-looking and his hair more lush. He loved emoji, especially the blue butterfly, which you can find on display in the Chicago Deciem store as an homage, and his emails were some of the most entertaining I’ve ever read. He could perfectly mimic legalese but with rhymes and clever wordplay. Even the most sarcastic or brief notes were signed “Smiles” or “Hugs” — which could be read as sincere or sinister, depending on the tone of the email — whether they were to his friends or Leonard Lauder, Estée Lauder’s son and the chairman emeritus of her namesake company.

I first met Brandon when I moderated a beauty panel he was speaking on in late 2017. I was excited to talk to him about the company, but had no clue just how much contact we’d have or how much my professional life would revolve around him over the next year. I didn’t like him necessarily, but I was still drawn to him. He was funny sometimes, and unpredictable most of the time. He had a lot of charisma, but he could also be cruel, lashing out at journalists, social media followers, and his employees.

Brandon’s troubles began in earnest in January 2018, when the company was called out by Redditors for seemingly picking a fight with prestige skin care company Drunk Elephant over marula oil prices. Their evidence was a social media ad that read, “One would have to be drunk to overpay for marula.”

Brandon apologized to Drunk Elephant via the Deciem Instagram — he had always contributed to the brand’s long, rambling captions, but had officially taken over the account around this time — and then the tone of his posts got weirder. While on a trip to Morocco, he posted pictures of garbage and a dead animal. He also ended a manufacturing relationship with Tijion Esho, a British dermatologist for whom Deciem produced lip products, on the public brand’s Instagram. Over the next few months, his social media antics became the beauty internet’s favorite reality show.

I became fascinated by Brandon and Deciem’s trajectory, breaking several stories about the company, and appearing on TV as a Deciem expert. During this tumultuous stretch, Brandon and I frequently saw each other in person, spoke on the phone, and emailed. Most brands keep a tight PR leash on their founders, never allowing direct access to them. But he wanted to speak to the press and would talk to me whenever I asked. He often forwarded me correspondence about company business. He could be defensive about pieces I’d written; other times, he’d tell me gossip about employees at the company. Some of the emails he shared were incredibly personal and salacious. As the year progressed, he started CC’ing other journalists, bloggers, lawyers, government agencies, and entire teams of people at retailers and companies Deciem worked with on long, confusing diatribes.

In February, after being contacted by several former employees, I reported on brewing issues at the company, including allegations of bullying by Brandon and Riyadh Swedaan, the warehouse manager at the time. (After Brandon’s death, Riyadh told the National Post that they had been a couple; the paper noted Brandon had publicly denied being gay. Riyadh is no longer with the company, according to his LinkedIn; he declined to speak to me for this story. Deciem did not provide more details on the situation.)

Soon after, Brandon fired Nicola. Nicola had been one of Brandon’s very first and most-prized Deciem employees. He hired her away from her position as a buyer at UK drugstore chain Boots when she was in her early twenties to be a brand director at Deciem. Within six months, he had elevated her to co-CEO. After Nicola’s exit, the newly-hired CFO Stephen Kaplan — a veteran finance pro in the consumer goods space and someone the team affectionately called the “adult in the room” — subsequently resigned, upset that she had been terminated. Deciem lost accounts at Sephora and some of its early smaller retailers as a result of the instability at the company.

Brandon became more defiant, and the ensuing months were chaotic. He posted disturbing Instagram videos to both his personal and the company accounts, routinely insulted Deciem’s followers, and became ever more paranoid, asserting people were following him and alluding to “financial crimes” within the company. He was hospitalized several times but was never kept long; he told Canada’s Financial Post that he had used crystal meth in the past. His exploits captivated the press, which compared him to Elon Musk and Donald Trump. At one point, QAnon got involved when Brandon started tagging the president in posts.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19780683/SP_6.jpg)

I grew increasingly concerned about Brandon and others at the company, who I had gotten to know in the course of my reporting. Employees and people connected with the brand spoke to me off the record to tell me how worried they were, too. I’d never encountered anything like this in my near-decade as a journalist. My editor and I constantly analyzed events and emails to decide if they were actually newsworthy or tabloid fodder. I often asked Brandon if he was okay, if he had someone to talk to during those times he seemed particularly distressed, but he would just get angry at me. People close to him told me he reacted similarly to them.

In October, Brandon announced on Instagram that he would be shutting down Deciem. Estée Lauder went to court to get him temporarily removed from the company and procured a restraining order against him, preventing him from going near Estée Lauder properties and Leonard Lauder, who he had threatened. Nicola was appointed interim CEO when she was seven months pregnant; she brought Stephen back, too.

Mira Singh, Deciem’s director of retail, says that during this time her customer service team was dealing with 4,000 to 6,000 calls and emails a week, about three to four times the usual volume. Sales increased too, since customers were panicked the company was going to go out of business. They stocked up on their favorites, further stressing the company to keep up with demand. It led to theories that this was all a savvy marketing move to sell more products. Jo of the Deciem Chatroom says it was “one of the hardest years of my life.”

It was a difficult period for everyone involved with the company. Nicola hoped the extreme moves initiated by Estée Lauder would convince Brandon to seek treatment. “Nothing made a difference,” she says, getting a little teary. “You think maybe if he realizes he’s at the brink of losing things, that’s what it’s going to take him to get the help he needs.”

My last real conversation with Brandon was in the summer of 2018, during one of his visits to New York City, a few months before his ouster. He talked mostly about those supposed “financial crimes” and one of his longtime investors who he felt had wronged him. He was fairly incoherent, and at one point suggested that I not dig too much into the company anymore. The interaction left me feeling vaguely threatened and tremendously unsettled.

Before I exited the hotel lobby where we had met, he told me in a by-then rare moment of clarity and prescience, “The best managers are the ones that can be away and things continue. That’s how much I trust and love our team.”

About six months later, I broke the story of Brandon’s death, which then circulated widely in the mainstream press. The members of the Deciem Chatroom posted condolences and loving homages to Brandon in many languages. I was ready to never write about the company again.

Nicola is a petite blonde with an English accent who radiates empathy; there is an earnestness and innocence about her. Temperamentally, she is Brandon’s polar opposite. She tells me about her plans for the company at the 75,000-square-foot open concept office Brandon conceptualized and for which he purchased many of the interior elements before he died. Next to us is a plaid felt dog he bought at a design shop in Amsterdam, an old sewing machine, and a stack of books piled to the double-height ceiling. He envisioned walls of books instead of drywall, but instead there are these book pillars scattered throughout.

A year after Brandon’s death, Deciem’s supply still hasn’t caught up with the demand for its products, especially now that The Ordinary is sold at Ulta, Sephora, and twice as many other retailers as it was a year ago; it also has 35 of its own stores, which have been temporarily closed in the wake of the coronavirus crisis. Up until mid-March, the company was in the process of adding more equipment to its factory, shoring up its safety measures, and looking at the potential of opening up another manufacturing facility down the line.

Meanwhile, it has discontinued or paused some of its early brands, though it plans to launch a body care brand called Loopha and a line for babies and sensitive skin-having adults called Hippooh. Before those, it hopes to debut a brand later this year consisting of inexpensive “powdered extracts.” The company also has plans to release the signature scent that is sprayed in every Deciem store as a fragrance, called Shop. It’s been a fan request ever since the stores opened. Deciem very much wants to continue to be an incubator and find its next The Ordinary.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19780684/SP_7.jpg)

The landscape has both bent to Deciem’s will and become more competitive since it hit the scene, and I’ve seen a marked change in how brands price and market their products. Legacy brands like L’Oréal have found themselves playing catch-up, hiring Eva Longoria to teach us how to pronounce HY-A-LUR-ON-IC acid in commercials, for example, two years after Deciem released the Ordinary. It’s now expected that brands share full ingredient lists online and even concentrations of active ingredients. Beauty start-up darling Glossier faced some backlash for this in 2018 for not revealing the exact proportions of different types of acids in one of its products.

Copycats have followed, too. Brands like The Inkey List and Good Molecules launched with similar concepts and price points. LVMH, the luxury conglomerate that owns Dior and Sephora, invested in Versed, an Ordinary-like skin care brand sold at Target. At the end of January, the New York Times published a story entitled “The $20 Luxury Face Cream.” The Ordinary is mentioned, but only at the very end, as part of a group of many. None of this has stopped the company from its goals of continuing to upend the beauty industry.

The fact that the company is thriving is a testament to Nicola’s perseverance and the loyalty she’s inspired both within the company and in outside entities like Estée Lauder and the brand’s many new retail partners. The way she carries herself has changed a bit since we last spoke in 2018. She walks with more confidence. She knows she’s in charge.

After Brandon fired her, she gave an interview to Elle in which she was unwavering in her dedication to the company and its founder, to the extent that the writer compared the interaction to talking to someone “rescued from a cult.” Current employees rave about Nicola too, but the tone is different. They express relief that she is there. There’s a genuine warmth.

“I was at the point where I couldn’t take it anymore and she was my saving grace,” says Mira the retail director, who was one of Deciem’s original employees. “She was the only person who had the capability to navigate the storm and really keep those strong values.”

Every single person I talk to speaks about her in superlatives: “wonderful,” “extremely calm,” “superhuman.” It’s genuine, and something that is impossible not to feel when you meet her. You want to hug her.

The first thing Nicola did when she came back after Brandon was removed but before he died was to implement employee perks like the ability to work from home, days off for birthdays, and free lunches. “We wanted to show love back to the team that showed us loyalty and commitment during the hard times,” she says. During the coronavirus closures, store employees are being paid and corporate employees are working from home.

Now there is a real HR team and a mental health program called “Hugs,” so named for Brandon’s email sign-off. Deciem is going to launch a podcast series this spring exploring mental health, because the team still wants to understand what happened to Brandon as part of its “healing journey.” They plan to donate $100,000 to the mental health charity of choice for each expert they have speak on the podcast. They hope to do 10 episodes.

I ask Nicola what she thinks Brandon would make of this new iteration of Deciem, which is decidedly corporate and well-run, and also prosperous.

“I think he’d be proud that we’ve retained a culture where the passion, the energy, the ideas, the ownership, the love is all still there. But we’ve fostered it in a way that can be sustainable and that is welcoming to new people and new talent,” she says.

“When I look at how this year started, the lowest of the low in the worst possible circumstances and I look at how we’re ending, with record-breaking months …” she trails off, and smiles to herself.

I didn’t think I would write this story. It wasn’t until Brandon’s death that I realized the toll reporting on his decline and its effect on his company and employees took on me. I was supremely exhausted and terribly sad. I stopped following the brand while it rebounded and continued to make waves in the industry. I didn’t really want to talk about it or him anymore.

My first career was as a nurse practitioner with a specialty in pediatric oncology, taking care of the sickest of kids. To do that job, you need a bit of a callus over your emotions or you can’t be effective in your work; toward the end, I was showing up crying every day. Reporting requires a not dissimilar distance. You can’t get attached to your sources. You’re there to tell stories, not be a part of them. But stories — even ones about businesses — are ultimately about people, and sometimes those people are in pain. It can be tough to reconcile.

Ultimately I couldn’t stay away from Deciem. I needed to understand more about Brandon, and I did admire what he had built. I started poking around into his early business dealings again, but couldn’t put together a comprehensive story, at least not one anyone would corroborate. I wondered how everyone at the company was holding up. I began seeing headlines that the brand was returning to Sephora. Positive profiles of Nicola appeared. I wanted to finally see the Deciem headquarters, to which Brandon had invited me many times. I wanted closure.

During my trip to the new offices, I kept expecting Brandon to come bounding down the staircase. My visit was hardwon, a product of six months of conversations with the company. Deciem is less transparent than it used to be, but it’s also more resilient. It’s no longer “abnormal,” as Brandon would fondly say. It’s the new normal.

Author: Cheryl Wischhover

Read More