Researchers are changing how they study the risks of alcohol — and it’s making drinking look worse.

A couple of drinks a day aren’t bad for you and may even be good for you.

Right?

That’s been the message — from researchers, governments, and beverage companies — for decades. And as a result, many of us don’t think twice about tossing back a couple of glasses or wine or a few beers after work.

But maybe we should. Because it turns out the story about the health effects of moderate drinking is shifting pretty dramatically. New research on alcohol and mortality, and a growing awareness about the rise in alcohol-related deaths in the US, is causing a reckoning among researchers about even moderate levels of alcohol consumption.

In particular, an impressive meta-study involving 600,000 participants, published in April in The Lancet, suggests that levels of alcohol previously thought to be relatively harmless are linked with an earlier death. What’s more, drinking small amounts of alcohol may not carry all the long-touted protective effects on the cardiovascular system.

“For years, there was a sense that there was an optimal level which was not drinking no alcohol but drinking moderately that led to the best health outcomes,” said Duke University’s Dan Blazer, an author of the paper. “I think we’re going to have to rethink that a bit.”

Alongside this study have come disturbing reports of the alcohol industry’s involvement in funding science that may have helped drinking look more favorable, as well as a growing worry that many people are naive about alcohol’s health effects. How many people know, for example, that as far back as 1988, the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer designated alcohol a level-one carcinogen? Some say too few.

Maybe it’s time that changes — with some caveats, as usual.

The “French paradox,” and why researchers thought a bit of alcohol was good for you

The story of light drinking as a healthy behavior started to take off in the 1990s, when many researchers believed red wine might be a magical elixir. This idea was known as the “French paradox” — the observation that the French drank lots of wine, and despite eating a diet rich in saturated fat, had lower rates of cardiovascular disease.

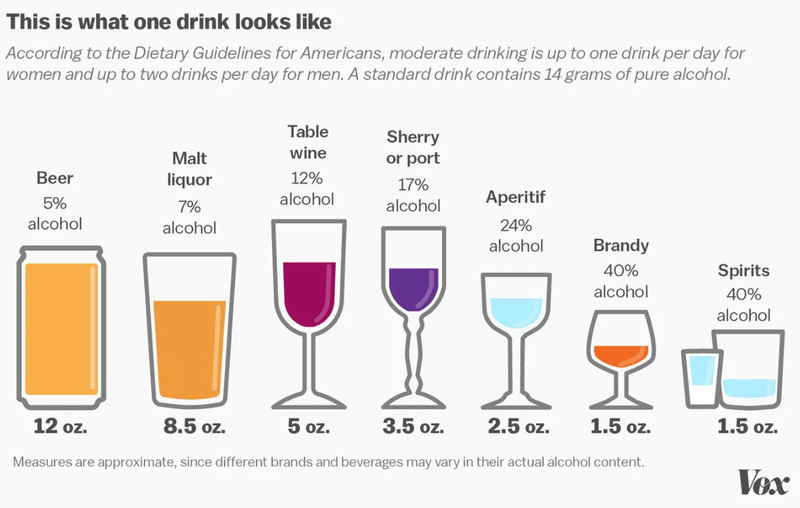

Researchers have since discovered it’s more than just their wine consumption that sets French people apart. But the red wine idea was replaced by a narrative suggesting drinking small amounts of any type of alcohol — no more than one drink a day for women, two for men — appeared to be linked with modest health and heart benefits.

In long-term observational studies comparing drinkers and non-drinkers, light to moderate drinkers (who imbibed about one to two units of alcohol a day) often had better health outcomes compared to non-drinkers and heavy drinkers. They had lower rates of heart disease and heart attacks and lived longer. Moderate drinkers also had lower rates of diabetes, another important risk factor for heart disease (although this result is less definitive).

But there was a problem with many of these studies: They compared drinkers to non-drinkers, instead of comparing only lighter drinkers to heavier drinkers. And people who don’t drink are pretty fundamentally different from drinkers in ways that are hard to control for in a study. Their lives probably look dissimilar.

Most importantly, they may be sicker at baseline (perhaps they quit drinking because of alcoholism, or because of a health issue like cancer). And something in these differences — not their avoidance of alcohol — may have caused them to look like they were in poorer health than the moderate drinkers. (This became known as the “sick quitter” problem in the world of alcohol research.)

Lately, researchers have been trying to overcome that problem by comparing lighter drinkers with heavier drinkers. And the benefits of modest amounts of alcohol wash away.

The upper safe limit for drinking may be lower than you think

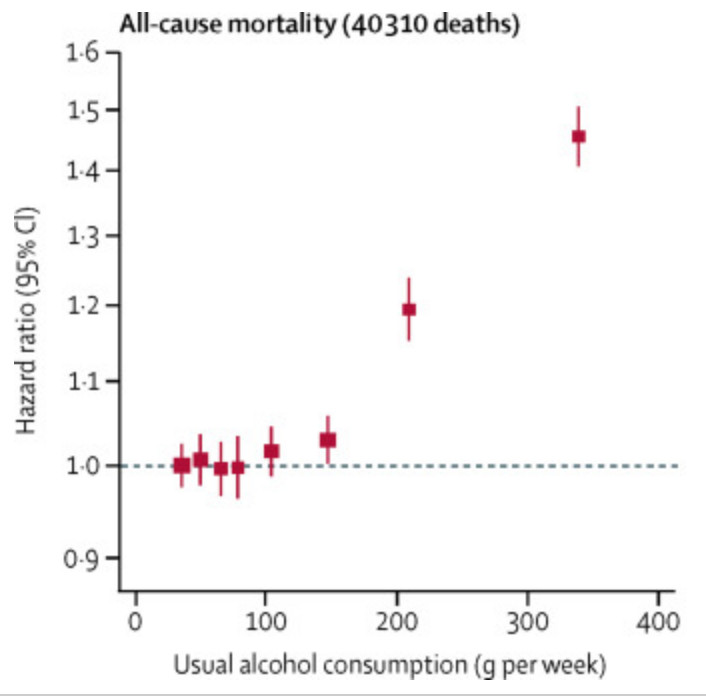

The most important new study on this was just published in The Lancet. Researchers brought together data from 83 studies in 19 countries, focusing on nearly 600,000 current drinkers (again, to overcome the “sick quitter” problem). They wanted to tease out what level of drinking was associated with an increased risk of death and cardiovascular disease.

Javier Zarracina/Vox

Javier Zarracina/VoxTheir findings were stark: Drinking more than 100 grams of alcohol — about seven standard glasses of wine or beer — per week was associated with an increased in risk of death for all causes, they concluded. In the US, the government suggests men can drink double that amount — up to two drinks per day — but advise women who are not pregnant to drink up to one drink per day.

A person’s risk of death shot up as they drank more. The researchers used a mathematical model to estimate that people who consumed between seven and 14 drinks per week had a lower life expectancy at age 40 of about six months; people who drank between 14 and 24 drinks per week had one to two years shaved off their lives; and people who imbibed more than 24 drinks a week had a lower life expectancy of four to five years.

You can see the risk increase in this chart here:

Lancet

Lancet“We wanted to find how much alcohol people can drink before they started being at a higher risk of dying,” said the lead author on the study, Cambridge University biostatistics professor Angela Wood. “Our results suggest an upper safe limit of drinking of around 100 grams of alcohol per week for men and for women. Drinking above this limit was related to lower life expectancy.”

Again, that’s different from the US guidelines, which suggest men can drink double that. The recommended upper limits of alcohol consumption in Italy, Portugal, and Spain are about 50 percent higher than the seven-drinks-per-week threshold the paper revealed.

The researchers also estimated that men who halved their alcohol consumption — from about 14 drinks per week to about seven — might gain one to two years in life expectancy.

What’s more, because they looked at so many studies on so many people, they were able to tease out alcohol’s effects on a number of measures of cardiovascular health — heart attack, heart failure, stroke. They found moderate alcohol consumption — around seven to 14 drinks per week — was associated with a heightened risk of cardiovascular disease according to some of the measures they looked at, including stroke, aortic aneurysm, and heart failure. These risks were generally higher for the people who drank more.

The exception was non-fatal heart attacks. The more people drank, the more their risk of heart attack went down. The researchers thought this may be driven by the fact that people who drink more tend to have high levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol — or the “good cholesterol” — which could put them at a lower risk of dying from a heart attack.

But that benefit should be balanced against alcohol’s other cardiovascular risks, including stroke, aortic aneurysm, and heart failure, said Eastern Virginia Medical School researcher Andrew Plunk. “Even though there might be some benefit for heart attacks, the other risks associated with it wash that out,” he added.

Newer research is finding similar associations with moderate levels of drinking. In a forthcoming paper, posted to BioRXiv, researchers took a similar approach to tease out the risks of drinking — using moderate drinkers instead of non-drinkers as the reference point to circumvent the “sick quitter” problem once again. The paper is only in pre-print and still needs to be peer-reviewed, but for now, its authors came to similar conclusions as the Lancet study, even though they used a different set of data.

More specifically, people who had one to two drinks four times or more weekly had a greater risk of dying from all causes than those who drank one to two drinks at a time weekly or less. And again, there was no difference between male and female study participants, which contradicts US government guidelines.

“When the reference point is never-drinkers, it looks like you can drink a lot before you have an increased risk,” said Washington University School of Medicine substance dependence researcher Sarah Hartz, the lead author on the BioRXiv pre-print. “But if the reference is the lightest group of current drinkers, it looks like any amount of drinking will increase your risk.”

“What we need to keep in mind is that alcohol is dangerous”

Before you empty out your liquor cabinet, however, there are a few important things to keep in mind. Nutrition science — including research on the effects of alcohol — is still in its infancy. There’s a lot even the best studies are forced to leave out. What were the lives of the study participants like? How do they eat? Where did they live? Did they exercise?

The supplementary material in the Lancet paper suggests these and other potential confounding factors may have been pretty important in determining people’s alcohol-associated health risks.

For example, in a subgroup analysis on the effects of alcohol by alcohol type, the Lancet authors found that spirit and beer drinkers seemed to have a higher risk of death and cardiovascular disease compared to wine drinkers. But they also found that beer and spirit drinkers looked pretty different from the wine drinkers: They were more likely to be lower income, male, and smokers and to have jobs that involved manual labor, compared with the wine drinkers.

“These findings suggest that the heavy beer consumption is part of an unhealthy lifestyle that is more frequently seen among people with lower socioeconomic status,” said Cecile Janssens, a research professor of epidemiology at Emory University. “Unhealthy diet, smoking, less exercise, less access to health care, etc., might all contribute to the higher risks.”

So you’d need to take these other factors into account to truly understand the risks of alcohol consumption, and the study didn’t.

“My major concern with the study is its inability to control for many confounders,” said Aaron E. Carroll, a physician and author of the book The Bad Food Bible. “Race is a big one — although they analyzed this in the appendix. So is socio-economic status. You also can’t ignore other dietary issues, exercise, and other factors which are related to disease and mortality.”

Failing to account for these factors could have exaggerated alcohol’s effects. It’s also possible that just cutting back alcohol, in this context, wouldn’t make much of a difference in life expectancy for some people.

“I’m not going to argue alcohol is good for you,” Carroll added. “It might be in preventing some [cardiovascular] outcomes. But there’s a gray zone in there as to where the damage starts to happen. I bet it’s very individual-dependent, and confounded by many, many other factors in an individual’s life.”

In a great tweetstorm, Oregon Health and Sciences University assistant professor Vinay Prasad explained additional limitations with this study, and why so much of nutritional science isn’t helpful at giving specific health advice. He suggested people use common sense instead to guide their decisions about how much alcohol is too much:

A couple weeks ago I said these HARSH words about a recent Lancet study & the media coverage where the authors argued more than 5-7 drinks a wk (100g/wk) was too many

I took heat

Well, I meant it then, and I mean it now.

And here is the TWEETORIAL on this paper/ nutritional epi pic.twitter.com/wooPfENRtD— Vinay Prasad (@VinayPrasadMD) April 28, 2018

Plus, Blazer said, “if you try to abide by every public health warning out there for every adverse effect, you’d have a miserable life. You wouldn’t do anything.”

Nonetheless, the new research is a reminder of something we often forget: Alcohol’s health effects are real, and they are serious. Excessive drinking can, over time, increase the risk of everything from liver disease to high blood pressure, dependency issues, and memory and mental health problems. Alcohol-related deaths have been going up in America: between 1999 and 2016, cirrhosis deaths rose by 65 percent — and the largest increases in that period were driven by alcoholic cirrhosis among young people, aged 25 to 34 years. As Vox’s German Lopez has reported, this is an underappreciated fact that often gets lost in the coverage of opioids.

(Here you can see deaths that are directly caused by the health consequences of alcohol, so the figures don’t include deaths from drunk driving, alcohol-related murder, et cetera. If it did, the death tally from excessive drinking use would now be closer to 90,000 per year).

“Not a lot of people know alcohol is a level-one carcinogen,” Harvard Medical School addiction researcher John F. Kelly told me. Any amount of drinking is associated with an increased breast cancer risk — something journalist Stephanie Mencimer admitted in Mother Jones she didn’t appreciate until she found out she has stage-two breast cancer.

“While doctors have frequently admonished me for putting cream in my coffee lest it clog my arteries … not once has any doctor suggested I might face a higher cancer risk if I didn’t cut back on drinking,” she wrote. For men and women, drinking is also known to increase the risk of mouth, throat, esophagus, liver, and colon cancer.

But when the weekend rolls around, and you want to cut loose, it’s not easy to face up to these facts. Alcohol is a huge part of our culture, and the problems it can carry aren’t always easy to swallow. But these new studies should sound a cautionary note, Blazer said.

“What we need to keep in mind is that alcohol is dangerous — and the danger of alcohol doesn’t receive the attention it deserves.”

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated the stage of Mencimer’s breast cancer.

Read More

https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/community_logos/52517/voxv.png