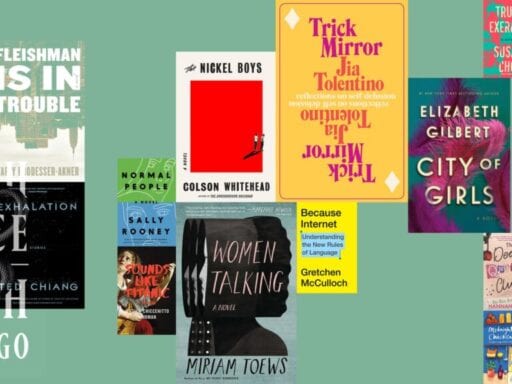

Our book critic’s 15 favorite books of 2019 include Irish schoolkids in love and lesbian necromancers in space.

Over the four years I’ve been writing these “best books of the year” lists as Vox’s book critic, I’ve realized the lists aren’t really about what the publishing landscape looks like in a given year. They’re about which tiny slice of the 2 million books published every year I’ve chosen to give my attention to, and which tiny slice I’ve chosen to point your attention to as well.

So please don’t take the following list as a definitive or exhaustive record of all the books that came out in 2019 that are worthy of your time. Instead, here are 16 books from the year’s 2 million that I am glad I gave my attention to: books that made me laugh or cry, that made me better understand the world or made the world feel like a nicer place to live in. I hope they can do the same for you, too.

Fiction

Fleishman Is in Trouble by Taffy Brodesser-Akner

Fleishman Is in Trouble takes the classic divorce novel and gently, devastatingly turns it inside out. It centers on Toby Fleishman, a middle-aged New York doctor who is in the process of getting a divorce from his wife, Rachel. True to the divorce novel genre, Fleishman spends a lot of time talking about how Rachel is a shrew and about all of the exciting kinky dating Toby’s doing now that he’s free of her — but unlike what you’d see in the classic divorce novel format, Toby is not the narrator of Fleishman Is in Trouble. A woman is telling his story. And as the novel goes on, women slowly begin to take center stage, and tell more and more of the story that Toby believed was his alone.

Dead Queens Club by Hannah Capin

There’s a certain kind of kid who gets obsessed with the six tragic wives of Henry VIII, who picks one of the queens to be their particular favorite in the same way that other kids pick favorite sports stars. (I myself was an Anne of Cleves girl; Anne Boleyn was for basics.) I think it’s the combination of glamour and complete grossness that makes the wives so compelling: These six women had their lives absolutely ruined by one tiny petty man, and that is horrifying, but also they got to wear really pretty gowns and they all had crowns.

Dead Queens Club, a YA novel that reimagines the wives as a modern-day teen girl gang, reads like it was written specifically anyone who once was or currently is one of those kids. Narrated by Cleves (my beloved), it allows the various homecoming queens and prom queens who have dated Henry — the prom king and football star of Lancaster High — to band together and get their revenge, once and for all. The results are incredibly cathartic.

Trust Exercise by Susan Choi

Reading Trust Exercise, I felt as though it wanted to hurt me. It wanted to trick me and pull the rug out from under me and make me feel foolish and bruise my heart, and it succeeded, and I am so glad that it did.

Trust Exercise, which won the 2019 National Book Award for fiction, follows a group of kids at a high-pressure drama school, tracing all the ways in which their teachers take advantage of their trust. But it also manipulates our own trust as readers, again and again. It pushes past all the old clichés you think you understand about unreliable narrators to make us rethink the fundamental contract between novelist and reader.

A novelist’s job is to tell the reader a lie and make the reader believe that it is the truth. But what happens when that lie is mixed with just enough truth to hurt?

City of Girls by Elizabeth Gilbert

City of Girls is a joyous book to read, a genuine romp of a story. It’s about a pretty young Vassar dropout named Vivian who moves to New York City in 1940 to have adventures. Immediately, she finds herself enmeshed in the city’s cheerfully seedy theatrical underbelly of hack musicals and showgirls, and proceeds to have an absolutely delightful time, right up until everything comes crashing down.

Deadpan Vivian is an immensely endearing narrator, but what has really stayed with me since reading City Girls are the clothes. The book’s clothing descriptions are so vivid and so compelling that they are almost their own character — and it’s all fully justified, because Vivian is a dressmaker who reads people’s personalities by looking at their wardrobes. But really, who needs justification when the ends are so much fun?

Normal People by Sally Rooney

Look, I am very sorry if you are sick and tired of seeing Normal People on so many year-end lists, but the fact is it’s fantastic and it would be journalistic malpractice for me to leave it off.

Normal People is about two teenagers, Connell and Marianne, who fall in love when they are in high school. Connell is popular and Marianne is an object of disgust at their school, and so they keep their relationship a secret; when they go to college, and their social statuses flip, that early secrecy continues to haunt their relationship and its power dynamics.

Sally Rooney writes the kind of cool, precise prose that generally doesn’t lend itself to genuine emotions, but Normal People is full of feelings. It feels tenderly toward its two young lovers, no matter how many mistakes they make, and they in turn are tender toward each other, no matter how badly they might treat one another. It’s rare that a book this smart will allow its readers to believe in love, but Rooney pulls it off without a hitch.

Women Talking by Miriam Toews

2019 was the year that a lot of the books that were written in 2017 as the Me Too movement took off finally came out in print. Which means 2019 delivered a lot of books thinking about rape and sexual violent and how we talk about all of the above. Women Talking is easily the best of all those books.

It concerns the women of a Mennonite colony in Bolivia who from 2005 to 2009 were the target of a string of serial rapes. Its (fictionalized) story begins after the rapes are over and the perpetrators have been discovered, and its question is this: Now that we all know — now that the story is out there, now that it’s very clear that we live in a culture of sexual violence toward women — what do we do? Where do we go from here?

Toews handles her tricky subject with grace and levity, but she never forgets how deadly serious it is. Nor does she let her readers forget that no matter what comes next, the worst thing that we could possibly do is let people go on as they always have, not running away or fighting back, but instead doing nothing at all.

Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead

Structure tends to get short shrift in book reviews. We talk about lyrical sentences and compelling characters and shocking twists all the time, but so often we forget to look at the part of the book that holds all of these elements in balance: the story structure.

Nickel Boys, about two black teenage boys stuck in a hellish reform school in the Jim Crow south, has a fucking beautiful story structure. It’s deceptively simple, just a classic three-act arc, but it’s so clean that each act break feels as though it was cut with a scalpel. That is why the characters of this book feel so weighty and consequential, in turn — and why it feels so devastating when Whitehead eases his plot twist out into plain sight.

Science fiction and fantasy

Ninth House by Leigh Bardugo

Ninth House is the kind of book you can read like you’re a kid again. It’s so immersive that you can lose yourself in it, as though you’re 8 years old, reading propped up on your elbows on your parents’ living room floor, and there is nothing in the world outside the pages of your book.

Ninth House is about a woman named Alex who can see ghosts. Alex has spent her life unable to understand her gift, terrorized by the ghosts that surround her and taking refuge in drugs. But then she lands herself a job as a ghost wrangler at Yale, going undercover as a student on Yale’s lush, haunted campus. And suddenly Alex’s future opens up wide in front of her. Assuming she can survive her job.

Alex is a joy of a protagonist, a con artist with an iron will who’s always working some angle, but what’s most compelling about this book is Bardugo’s ghost-ridden, luxurious Yale. Bardugo is lavish with her details, and her version of the school feels like the kind of world you can walk into, equal parts enchanting and corrupted.

Exhalation by Ted Chiang

Sci-fi author Ted Chiang writes the only time travel stories I have ever read that don’t end with me squinting at the page and saying, “I mean … I don’t think that’s really consistent with the rules you just established, but I guess?” Chiang’s rules are always consistent, they always make sense, and they are always exploited to showcase their full and devastating consequences.

The same is true for the rules of all the imagined technologies Chiang is working with in this short story collection — he meticulously observes not just the rules he sets for time travel, but the rules of robots, of enhanced memories, of parallel worlds. Chiang’s technologies are always fully rooted in existing scientific principles, and he is always willing to think through the best and the worst ways in which they could possibly be used. The effect is to make every story in Exhalation feel achingly possible.

Gideon the Ninth by Tamsyn Muir

Gideon the Ninth swallowed me up. For two days, I could do nothing but read Gideon the Ninth and think about Gideon the Ninth, and then when I finished it, I spent the rest of the week telling everyone I knew to read it so that I could find someone to discuss it with. “It’s about lesbian necromancers in space!” I kept saying.

But the fun of the high-concept premise is only part of what makes Gideon the Ninth so good. Tamsyn Muir writes the kind of rich, lush prose that you can roll around on your tongue, all high gothic imagery that’s periodically punctured by the appealingly flat, down-to-earth voice of sweetly basic jock Gideon. And her character dynamics are so beautifully complex that months after I read this book, I’m still not sure whether I think her main characters are in romantic love, or not. I just know that they’re the most important people in the world to each other, and I buy their connection absolutely.

The Secret Commonwealth by Philip Pullman

There’s an image in The Secret Commonwealth that haunts me. Our heroine Lyra has met a man who has lost his dæmon, the talking animal companion who is his soul, and he tells her that he keeps imagining that he’ll see his daemon again some day, but not with him: “that I will see her with a man who is me, who is my double.” There are so many sad layers to that idea, so much self-loathing and melancholy and terror, that it took my breath away when I read it, and since then it has kept emerging from the back of my head like a song you can never escape.

With the His Dark Materials series of the late ’90s, Philip Pullman introduced the world to the idea of the daemon. It was an immensely appealing fantasy: a perfect companion who knows and understands you intimately because they are you, a part of yourself who can keep you company. But in the new companion series, The Book of Dust, of which The Secret Commonwealth is the second volume, Pullman has been developing the dark side of the daemon fantasy. If you can see yourself and talk to yourself, what happens if you don’t like yourself very much? What happens to your relationship with your dæmon when you are depressed? Lyra starts to answer that question in this volume, and it’s devastating.

Nonfiction

Sounds Like Titanic by Jessica Chiccehitto Hindman

What a stunning memoir this is. Jessica Chiccehitto Hindman spent four years of her life working as a fake concert violinist, hired to play her violin inaudibly behind a fake mic at craft fairs and malls, while a pre-recorded performance blasted out of the speakers behind her at an audience that never knew the difference. It’s a killer premise, and Hindman develops it to its full potential, delving into all the details of how physically painful it was for her to spend eight hours a day pretending to play her violin, how much it messed with her head to keep lying to her audience day after day after day.

But Sounds Like Titanic is more than just its wacky premise. It’s also an examination of post-9/11 America, and all the ways a country in shock developed a bottomless appetite for comforting, meaningless lies. And Hindman, who became a fake violinist after her Plan A — to be a foreign correspondent in the Middle East — fell through, knows exactly how to build the connections that make her argument sing.

Because Internet by Gretchen McCulloch

I am obviously never laughing out loud when I type the acronym “lol,” and probably neither are you, if you spend much time online. (When I actually laugh out loud, I type “actual lol.”) But sometimes I do wonder what I’m doing when I type “lol,” what kind of significance that weird little acronym has picked up and what social work it’s doing for me that I rely on it so often, even when I’m not laughing.

In Because Internet, the linguist Gretchen McCulloch explains “lol”: It’s an irony marker, she says. It shows up to soften sentences that might otherwise sound harsh, or when you’re asking for sympathy from a friend but you don’t want to sound too sorry for yourself, or when you’re flirting but you also want some plausible deniability. “Lol” has developed patterns and rules that we recognize on an unconscious level, and McCulloch has the linguistic training to figure out what those rules are and explain them to us — along with all the other weird ways we write on the internet.

Midnight Chicken by Ella Risbridger

Midnight Chicken is nominally a cookbook, but it’s the kind of cookbook you can read straight through, sitting in an armchair with a cup of tea at your side, just for the pleasure of the language. Ella Risbridger’s recipes work as recipes, but what makes them so lovely to read is the argument that they are making about food: that food is a celebration when you are happy, and a comfort and a reminder that life is worth sustaining when you are sad.

“This is a story of eating things,” Risbridger writes in the opening of the book, “which is, if you think about it, the story of being alive. More importantly, this is a story about wanting to be alive.” And it’s a joyous story to read.

Trick Mirror by Jia Tolentino

This debut essay collection by New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino is designed to force us to reckon with the problem that most of us know to be true but which we generally avoid thinking about in order to get through the day: Our culture will not allow us to survive without participating in systems we know to be inhumane and exploitative. We cannot live in this world without participating in sexism, in racism, in predatory capitalism, and often we participate in those systems not just because we have to but because we find it convenient and pleasurable to do so.

“The choice of this era,” Tolentino writes, “is to be destroyed or to morally compromise ourselves in order to be functional — to be wrecked, or to be functional for reasons that contribute to the wreck.”

And she makes her case in damning, exquisite detail, zeroing on everything from lunches at Sweetgreen to the Soho scammer, finding compromise everywhere she looks. Trick Mirror is a map to the systems that ensnare us all and how they work, and if it doesn’t find an escape anywhere, it at least gives us a way of talking about the things that hold us trapped.

Author: Constance Grady

Read More