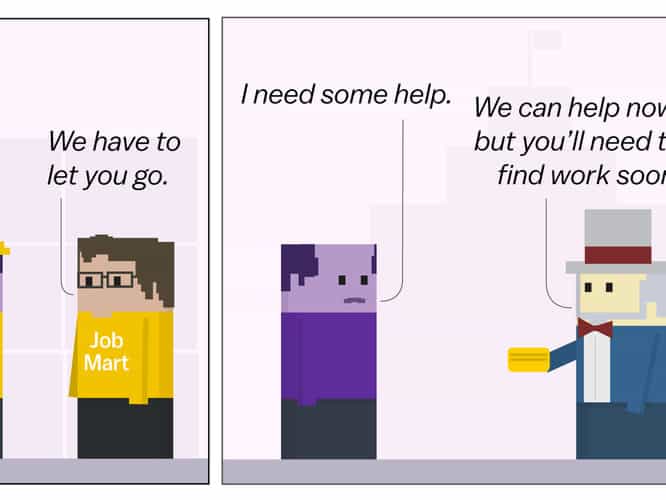

Should poor people be required to work to get benefits? This cartoon explains the merits behind the Republican push.

There’s another Republican push to make it harder for poor people to qualify for government benefits.

This push revolves around the idea of “work requirements” — that is, a requirement that people work in order to receive benefits like welfare, food stamps, and Medicaid, among others.

President Donald Trump’s economic advisers recently released a report arguing that work requirements build “self-sufficiency” and improve people’s lives. The Trump administration doubled down on trying to impose work requirements for Medicaid after a federal judge blocked the move in Kentucky. And House Republicans are pushing to impose stricter work requirements on food stamp recipients.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11539957/1.png)

Under current law, there are certain benefits that have work requirements.

For example, one program that currently has work requirements is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, often known as food stamps, which requires able-bodied recipients without dependents to work 80 hours a month or show they’re meeting other similar requirements.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11539961/2.png)

These requirements were implemented as part of the 1996 welfare reform signed by President Bill Clinton. Economists generally agree that the previous welfare program — created for white widows so they wouldn’t have to work — was designed to keep people from working, even if they disagree on what mechanism created this incentive. Work requirements aimed to fix that.

In recent years, some states with Republican legislatures, like Kansas, have implemented even harsher work requirements — and tougher penalties — for these programs.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11539965/3.png)

And now Republican leaders want to attach work requirements to more social services or make existing ones harsher.

- In January, the Trump administration allowed states to impose work requirements for Medicaid, which provides health care to Americans who are poor and disabled.

- In April, Trump told his Cabinet to find other social services for which they can impose work requirements or make existing requirements harsher.

- House Republicans passed a Farm Bill that imposes harsher work requirements on food stamps; the Senate stripped the changes to work requirements before passing their version. But House Speaker Paul Ryan still wants to get more stringent work requirement into the final bill.

Republicans aren’t saying everyone should work to get government help. After all, there are certain people who can’t work for good reason, including children, the elderly, and the disabled.

Instead, work requirements focus on “able-bodied” adults who aren’t working — which, for a program like Medicaid, is a tiny portion of recipients. Republicans make the argument that it’s unfair for capable people to receive taxpayer dollars without working for it.

Democrats, meanwhile, say it’s cruel to withhold basic necessities from people who need it — and that people aren’t necessarily choosing to stay out of work. We won’t resolve that debate here.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11760145/who_benefits_from_medicaid.png)

But there’s another argument both parties were making during the push for welfare reform in 1996, and that Republicans are making again now: that work requirements incentivize people to get back to work — and help people pull themselves out of poverty.

In fact, the nation’s top Medicaid official, Seema Verma, said that when we refuse to impose these requirements on people, we are exhibiting the “soft bigotry of low expectations.”

This argument has been put to the test. It has now been a couple of decades since the 1996 welfare reform that first instituted work requirements. And studying its effects, we find that it failed to achieve lawmakers’ stated objectives.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11539977/5.png)

Do work requirements push people to work more?

There’s a simple way to figure out if work requirements actually incentivize people to work: Take a group of people on welfare and randomly impose work requirements on some of them.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11539987/6.png)

This is exactly the experiment various groups ran in different cities in the lead-up to the 1996 welfare reform. A few years ago, LaDonna Pavetti at the Center for Budget and Policies Priorities (CBPP) reviewed the results of 13 of these experiments, which looked at recipients of cash assistance.

Pavetti found that in the first few years after imposing work requirements, people did work slightly more. But the gains were marginal, because most people worked even if work requirements weren’t imposed.

Work requirement supporters often cited the most successful test site — Riverside, California — where the employment rate among recipients rose 10 to 15 percentage points. But there was also one site where the employment rate decreased.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11737571/work_reqs_after_one_to_two_years.png)

Fast forward five years: Were people who were subject to work requirements still more likely to be employed? Not really.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11737589/work_reqs_after_five_years.png)

The researchers looked at this another way, by looking at whether work requirements led to more stable employment. The gains were small.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11737597/work_reqs_stable_employment.png)

In short, work requirements pushed people to work a bit more in the short term, but those effects faded after a few years.

Do work requirements help pull people out of poverty?

The long-view argument behind work requirements is that, if more people work, more can pull themselves out of poverty.

So the researchers tracked how people on welfare with work requirements were doing two years after the start of the experiment.

They found that work requirements caused poverty rates to barely budge, partially because even people who found work weren’t earning enough to lift themselves out of poverty. In addition, at half the experiment sites, work requirements caused more people to be in deep poverty.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11737731/work_reqs_poverty_rates.png)

More recently, Republicans in Maine and Kansas imposed work requirements for food stamps after they were waived during the economic downturn.

When the move caused a 70 to 80 percent reduction in childless adults participating in the program, they bragged that it made people less reliant on government.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11540013/13.png)

One year later, researchers followed up with people who were cut off from food stamps and found that their total income (which include earnings and food stamp value) had decreased 3 percent.

Work requirements didn’t pull people out of poverty. It made them poorer.

Work requirements could make it harder for people to pull themselves out of unemployment

The term “able-bodied” has historically been used to arbitrarily separate the people lawmakers feel are, and aren’t, deserving of public assistance.

There are legitimate reasons why an able-bodied person can’t find work, like having child care or elderly care responsibilities, undiagnosed mental illness, a lack of skills, or a criminal record.

This is why lawmakers carve out various exemptions, like saying people with dependents aren’t subject to the same requirements.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11540009/12.png)

But this is a highly arbitrary process, and marginalized people can slip through the cracks.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11760125/you_look_healthy_enough.png)

But on top of this fraught system, Republicans have made proposals to impose new or stricter work requirements. They want to expand work requirements to older people who didn’t used to be covered, while also requiring more work hours and frequent check-ins.

This added bureaucracy could mean recipients might be subject to administrative errors and procedural deadlines, adding pressure to an already fragile situation.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11540015/14.png)

Work requirements are trying to solve the wrong problem

The idea behind work requirements is that poor people are incentivized to stay out of work when given free government help. This might be true, though the effects are extremely small.

So are work requirements the answer to the problem? After reviewing the academic literature, Pavetti of the CBPP came to this conclusion: “Too many disadvantaged individuals want to work but can’t find jobs for reasons that work requirements don’t solve.”

She found people can’t work because they don’t have the skills to be employable, don’t have the social connections to find job openings, or have personal challenges.

In other words, if work requirements are trying to decrease unemployment, it’s assuming the wrong thing about the unemployed.

Last year, Brookings Institution researchers Martha Ross and Natalie Holmes analyzed what the out-of-work population looked like. They found that the biggest portion were less-educated people who should’ve been in the prime of their working lives:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11760135/out_of_work.png)

And there was a high probability these people were either foreign-born or had limited English proficiency:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11540023/17.png)

Even among the moderately educated there were common barriers, like needing to care for young children or a job market that no longer values their skill set.

In other words, there are actual problems with helping people find a stable job that pays a living wage. Ross and Holmes stressed the importance of understanding the specific situations of unemployed people. For example, an intervention for less-educated young people might be a bridge program, which helps students with poor academic skills prepare for college-level classes or occupational training programs. Other people might need job search assistance, career counseling, or a transitional job.

Work requirements don’t aim to solve any of those problems. Rather, it keeps basic human necessities hostage in hopes that it’ll scare poor people into being less poor.

Author: Alvin Chang

Read More