The fate of American democracy could rest with Brett Kavanaugh.

The Supreme Court handed down a brief order Monday night making it harder for voters in South Carolina to cast a ballot.

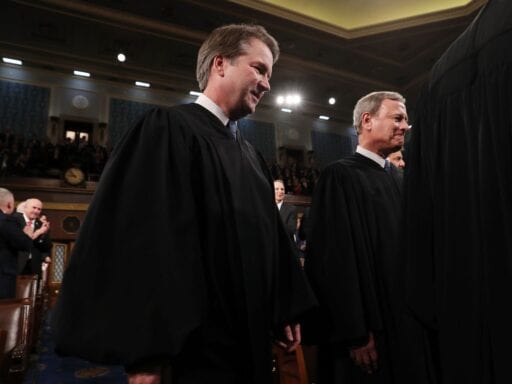

The Court’s order in Andino v. Middleton is only two paragraphs long, and it is accompanied by a concurring opinion from Justice Brett Kavanaugh that is only about a page long. Nevertheless, this short order, the dissenting votes of the three most conservative justices, and Kavanaugh’s brief opinion provide a great deal of information about how the Supreme Court is likely to handle disputes regarding a presidential election held amid a pandemic.

The Court’s decision in Andino reinstates a South Carolina law requiring absentee voters to have another person sign their ballot as a witness. A lower court which blocked this law reasoned that this requirement, applied in the context of a deadly pandemic, places too high a burden on voters who fear becoming infected with Covid-19.

The Supreme Court’s decision to reinstate this witness requirement is not surprising. Last July, in Merrill v. People First of Alabama, the Supreme Court voted along party lines to reinstate a similar requirement in the state of Alabama. Interestingly, no justice publicly dissented from the Court’s decision in Andino that South Carolina’s witness requirement must be reinstated — although when a party seeks a stay of a lower court order, sometimes dissenting justices quietly dissent without making that fact public.

Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Neil Gorsuch did note their dissents, however, signaling that they would have tossed out an unknown number of ballots that have already been cast.

Andino reveals that there is a meaningful divide between the extreme views held by these three dissenters, and the slightly more moderate views on voting rights held by Roberts and Kavanaugh. And it shows how Kavanaugh — whose vote would matter a great deal in a 6-3 Republican Court — is likely to treat litigation over the 2020 election.

The dissenting justices’ position is extraordinarily hostile to the right to vote

The position of the three dissenters — Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch — is astonishing. The lower court handed down its decision blocking the witness requirement in mid-September, and at least 20,000 voters have already cast a ballot in South Carolina.

That means that thousands of South Carolina voters cast their ballot while the lower court’s order was still in effect. It’s likely that at least some of these voters, acting under the entirely reasonable belief that South Carolina would comply with a federal court order, did not have their ballots signed by a witness — given that until Monday night, the state was subject to a federal court order requiring it to count ballots that were not witnessed.

Nevertheless, Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch would have ordered unwitnessed ballots tossed out even if they were cast during the period when South Carolina was bound by a court order. These three justices effectively required voters to anticipate that a federal court order would subsequently be stayed by an order of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Perhaps a voting rights lawyer familiar with the Supreme Court’s decision in Merrill could have warned such voters that a Supreme Court stay was likely in the Andino case, but the law typically does not require ordinarily voters to hire legal counsel simply to determine how they should cast their ballot.

In any event, Thomas, Alito, and Gorsuch’s vote reveals a consuming hostility to the right to vote. Voting rights plaintiffs, and their lawyers, should likely write off the possibility of these three justices doing anything to protect the franchise.

Kavanaugh’s stance is still hostile to the right to vote, but much less so than the three dissenters’ position

Because three members of an eight-justice Court voted to toss out already-cast ballots with no witness signature, we know that the other five justices did not vote for such a harsh outcome. Chief Justice John Roberts, Justice Kavanaugh, and the three liberal justices all voted to allow ballots “cast before this stay issues and received within two days of this order” to be counted.

Roberts did not explain why he voted the way that he did, but Kavanaugh did write a brief concurring opinion explaining why he thinks that ballots cast in the future must be signed by a witness.

In that opinion, Kavanaugh offers two justifications for his vote. The first is the Court’s decision in Purcell v. Gonzales (2006), which established that “federal courts ordinarily should not alter state election rules in the period close to an election.” Kavanaugh’s citation to Purcell suggests that he thinks that the lower court should not have changed South Carolina’s election rules less than two months before an election.

Kavanaugh’s other reason for reinstating South Carolina’s witness requirement is worth quoting at some length:

[T]he Constitution “principally entrusts the safety and the health of the people to the politically accountable officials of the States.” “When those officials ‘undertake[ ] to act in areas fraught with medical and scientific uncertainties,’ their latitude ‘must be especially broad.’” It follows that a State legislature’s decision either to keep or to make changes to election rules to address COVID–19 ordinarily “should not be subject to second-guessing by an ‘unelected federal judiciary,’ which lacks the background, competence, and expertise to assess public health and is not accountable to the people.”

Justice Kavanaugh says two significant things here. The first is that federal courts typically should not intervene to prevent voters from being disenfranchised during a pandemic. The decision about whether to alter state election laws to ensure that the coronavirus does not interfere with voters’ ability to cast a ballot primarily rests with state legislatures.

But Kavanaugh also states that this principle cuts in both directions. A state’s decision “either to keep or to make changes to election rules to address COVID–19” should generally be honored by federal courts. Thus, Kavanaugh appears to be signaling that the federal judiciary should permit states to make it easier to vote during the pandemic, should they choose to do so.

That’s bad news for President Trump, as Republicans have filed several lawsuits seeking to block state laws making it easer to vote, including a Nevada law providing for vote by mail, and guaranteeing that many ballots that arrive up to three days after Election Day will still be counted.

To be clear, Kavanaugh’s opinion is hardly good news for voting rights advocates, as it makes it clear that Kavanaugh will do nothing to block many laws that disenfranchise voters during the pandemic. With Republicans about to gain a 6-3 majority on the Supreme Court — and with three justices taking an extreme anti-voting stance in Andino — voting rights advocates will likely need Kavanaugh and Roberts’s votes to prevail in any case that reaches the Supreme Court.

But Kavanaugh’s opinion does suggest that the Supreme Court is more likely to take a position of indifference towards voting rights during the November election, rather than actively trying to sabotage Democrats at every possible turn.

There is still one live issue before the Supreme Court that isn’t discussed in Kavanaugh’s opinion. In Scarnati v. Pennsylvania Democratic Party, Republican lawyers ask the US Supreme Court to block a decision by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, which requires the state to count mailed ballots that arrive up to three days after the election.

The Purcell decision is generally understood to prevent federal courts from modifying state election law close to an election. It would be an extraordinary extension of Purcell to prevent state courts from interpreting their own state’s election law.

Indeed, it’s not entirely clear how many states could run elections under such circumstances, because disputes about the proper meaning of state election law are inevitable during election season. If state courts cannot interpret those laws, these disputes would go unresolved.

Kavanaugh’s opinion in Andino refers only to federal courts. It remains unlikely that even this very conservative Court will block a state supreme court’s decision interpreting that state’s own election law. But, until the Supreme Court rules in Scarnati, there is at least some risk that a majority of the justices will embrace the Republican Party’s position in that case.

Millions turn to Vox each month to understand what’s happening in the news, from the coronavirus crisis to a racial reckoning to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world: Contribute today from as little as $3.

Author: Ian Millhiser

Read More