After failing badly to meet a target of 45,000 refugees for 2018, the Trump administration is letting in no more than 30,000 next year.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announced Monday that the United States plans to bring no more than 30,000 refugees to live in the US in fiscal year 2019, which starts October 1.

30,000 is by far the lowest “ceiling” for refugee admissions in the nearly 40 years of the current refugee law. The only year that comes close is fiscal year 2018, when the Trump administration proposed a ceiling of 45,000. Both Trump years are a fraction of the pre-Trump standard for refugee admissions, which averaged 96,000.

The announcement happened with barely any fanfare: Less than an hour before Pompeo spoke, a Department of State press release was sent out saying that he would be delivering “remarks to the media” at 5 pm, without further details. Furthermore, the administration skipped the legally required step of consulting Congress before setting refugee levels (which the Obama administration also skipped in 2016 and the Trump administration only nominally complied with in 2017).

But the remarks — and the drop they announced — are huge.

Pompeo essentially attributed the latest reduction to strained resources, saying the administration was cutting back while it tries to deal with current asylum-seekers crossing into the US: “This year’s refugee ceiling reflects the substantial increase in the number of individuals seeking asylum in our country, contributing to a massive backlog of outstanding asylum cases and greater public expense,” he said.

That zero-sum logic reflects the Trump administration’s actions (it’s shifted officers from refugee cases to asylum cases) and its “America First” premise that refugees are a drain on public expense (contrary to what a suppressed 2017 government report found). But from a global perspective, refugee admissions and asylum processing are two sides of the same coin.

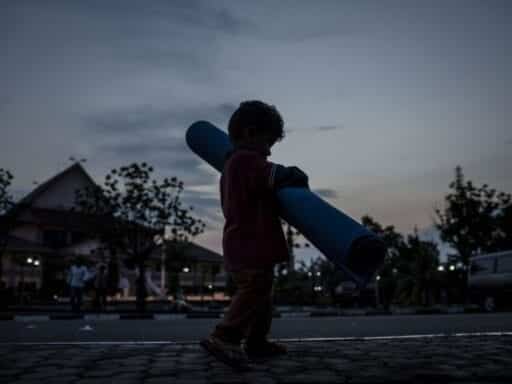

The reduction in US refugee admissions is coming in an era when more people than ever are displaced and when displacement generally lasts for years, if not decades. Countries around the world are being asked to step up and increase their commitment to refugee resettlement. The UN is finalizing a Global Compact on Refugees (which the US pointedly withdrew from in 2017).

The US has historically been the world’s leader in resettlement — anywhere between a third and a half of all refugees who’ve been permanently resettled since the end of World War II have come to America. But a year after radically reducing refugee targets, it’s radically reduced them again.

Will actual refugee admissions align with expectations — or will this set a downward spiral?

It’s almost misleading to talk about the US’s refugee ceiling for fiscal year 2018, though, because with days left in the fiscal year the US is less than halfway to meeting it.

As of September 17, the US had admitted 20,918 refugees of the proposed 45,000.

The Trump administration protests that the 45,000 level wasn’t a target — it was a maximum. However, administration officials (including L. Francis Cissna, the director of US Citizenship and Immigration Services, which interviews and processes refugees) have admitted that the 2018 ceiling was not in line with the actual pace at which the administration has ended up processing refugees.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13071927/Refugee_targets_vs._resettlementsV2.jpg) Javier Zarracina/Vox

Javier Zarracina/VoxPart of that’s been the result of the administration’s policies. The worldwide ban on refugee resettlement under the second iteration of the travel ban (as it was allowed to go into effect in modified fashion in June 2017) ended a few days into fiscal year 2017. But it was swiftly replaced with temporary near-total bans on refugees from a handful of specific countries, which happened to include countries that had sent thousands of refugees to the US in recent years — like Syria, Iraq, Iran, and Somalia. When those bans were lifted in January, the Trump administration announced it was expanding security processing for all refugee applications.

The raised bar for scrutiny of refugees — a longtime Trump campaign promise, out of fears that Syrian refugees would be a “Trojan horse” — has reportedly bottlenecked the system. The FBI is reportedly responsible for conducting separate security checks on every single refugee being considered for admission — without extra resources to process these checks. NBC News reported over the summer that in some cases, agents could complete only a few checks a day.

In the meantime, the Trump administration has pulled dozens of refugee officers — the people who are supposed to travel abroad and interview refugees in person as part of the application process — into temporary gigs interviewing asylum applicants who have arrived in the US (usually after the asylum-seekers have entered without papers and been detained).

The added capacity on asylum claims brings the Trump administration closer to its goal of moving through asylum cases as quickly as possible so that unsuccessful asylum-seekers can be swiftly deported. It also further reduced the administration’s capacity to meet its ceilings for selecting its own refugees from abroad.

The result, according to advocates, is that tens of thousands of refugees are languishing in the pipeline — and others are waiting in the US for family members who they haven’t seen in more than a year to meet them.

If the Trump administration actually takes its 2019 cap seriously and resettles close to 30,000 refugees, it will represent a substantial increase from 2018 levels.

On the other hand, if it takes the reduction from 45,000 to 30,000 as a reason to further reduce its capacity for refugee screening, it may fall as short of 30,000 next year as it did of 45,000 this year.

That’s what refugee advocates fear will happen. They know that the Trump administration doesn’t feel a global obligation to resettle refugees — because Trump himself has said so. He’s laid out a theory of humanitarian aid in which it’s the responsibility of nearby rich countries to help refugees go home (or, at least, that’s what he’s expressed when the refugee crisis is far from the United States). They know that the administration’s key players, including Chief of Staff John Kelly and senior policy adviser Stephen Miller, are suspicious of refugees — and that Miller has attempted to stop information about refugees’ contributions to the US from reaching the president and the public.

So for advocates (and for the hundreds of Americans who work for local nonprofits helping refugees acclimate to their new lives), the best-case scenario is that the new cap represents a new equilibrium, and America actually intends to resettle 30,000 refugees next year — a dimmer goal than the country has ever set.

Author: Dara Lind