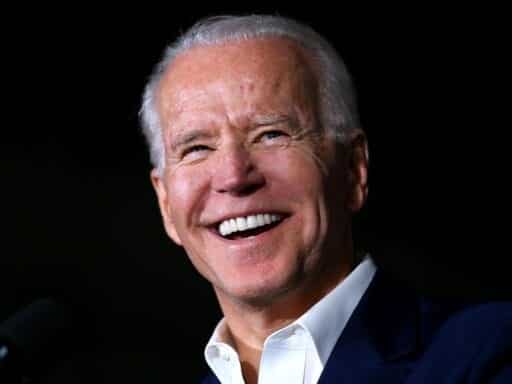

Political junkies don’t like Joe Biden, but voters do. And there’s a reason for that.

It’s time for a fresh look at Uncle Joe.

On Super Tuesday, Joe Biden broke the narrative that had defined the Democratic primary race. The surprise wasn’t that he won, though that was unexpected. It’s that he won new voters in a high turnout election — almost every state saw a turnout surge, and a Washington Post analysis suggests Biden won 60 percent of voters who didn’t cast a ballot in 2016.

“We increased turnout,” Biden said in his victory speech. “The turnout turned out for us!”

This is a result that requires some rethinking. Prior to Super Tuesday, the conventional wisdom was simple. Bernie Sanders was the turnout candidate, and Biden the uninspiring generic Democrat. You could see this in Sanders’ packed rallies, his diehard social media brigades, his army of individual donors — and in Biden’s inability to match those markers of enthusiasm. If new voters flooded the primary, it would be proof Sanders’s political revolution was brewing. But if the political revolution failed and turnout stagnated, Biden might slip through. What virtually no one predicted was Biden winning a high turnout contest. But he did.

So what did the narrative get wrong? As someone who believed that narrative, what did I get wrong?

In conversations over the past week, I’ve heard a few theories. I am not saying I fully believe these arguments, but given that some of them directly implicate my own blind spots, they’re worth considering.

Biden’s speech patterns offend the media. Voters don’t really care.

Biden has lost a step rhetorically. In debates, his answers have, to put it gently, a meandering quality. He loses his place, says the wrong thing, mixes up words, free associates. Without engaging the question of whether this reflects a lifelong stutter or a more worrying decline, the simple fact is that Biden performs worst on the metric that media professionals judge most harshly, and most confidently: clarity of communication.

But over and over again, we’ve seen that voters just don’t care that much about malapropisms and meandering rhetorical styles. Books — yes, plural! — were published mocking George W. Bush’s garbled sentences. And Bush looks like Cicero compared to Donald Trump’s word salad. This, for instance, is a direct transcription from a 2015 Trump rally:

Look, having nuclear — my uncle was a great professor and scientist and engineer, Dr. John Trump at MIT; good genes, very good genes, okay, very smart, the Wharton School of Finance, very good, very smart — you know, if you’re a conservative Republican, if I were a liberal, if, like, okay, if I ran as a liberal Democrat, they would say I’m one of the smartest people anywhere in the world — it’s true! — but when you’re a conservative Republican they try — oh, do they do a number — that’s why I always start off: Went to Wharton, was a good student, went there, went there, did this, built a fortune — you know I have to give my like credentials all the time, because we’re a little disadvantaged — but you look at the nuclear deal, the thing that really bothers me — it would have been so easy, and it’s not as important as these lives are (nuclear is powerful; my uncle explained that to me many, many years ago, the power and that was 35 years ago; he would explain the power of what’s going to happen and he was right — who would have thought?), but when you look at what’s going on with the four prisoners — now it used to be three, now it’s four — but when it was three and even now, I would have said it’s all in the messenger; fellas, and it is fellas because, you know, they don’t, they haven’t figured that the women are smarter right now than the men, so, you know, it’s gonna take them about another 150 years — but the Persians are great negotiators, the Iranians are great negotiators, so, and they, they just killed, they just killed us.

Journalists who’ve based their professional lives on clear, crisp, stylish communication find it shocking when candidates get lost in rhetorical mazes of their own construction. But both Bush and Trump won the presidency. And Ronald Reagan won reelection in a landslide, even though he couldn’t recall what city he was in during the first presidential debate and admitted to being “confused.”

Biden’s most visible weakness in day-to-day campaigning, in other words, is a weakness the media consistently overrates, at least when it comes to election outcomes.

Nonvoters aren’t as ideological as political junkies

Lurking beneath the theory that high turnout would disadvantage Joe Biden is what we might call the “disappointed nonvoter thesis.” Scratch a political junkie and you’ll almost always find the same theory of turnout underpinning their plans: If only a candidate would say what I already think, but louder. This reflects the disappointment that the very engaged have with their leaders: practicing politicians have to appeal to mixed constituencies to win reelection or pass anything in Congress, and so they compromise their beliefs, sand down their edges, trim their ambitions.

The politically engaged perennially argue that the way to mobilize the nonvoters is to offer a clearer choice, rather than a muddled echo. Under this theory, Bernie Sanders is the clear turnout candidate, as his sharper and more ambitious agenda can mobilize nonvoters who don’t think either party speaks for them. Conversely, Biden is the business-as-usual choice.

In general, this strategy disappoints. The most famous “choice, not an echo” candidate, Barry Goldwater, lost in a landslide. And he’s the rule, not the exception. Political scientists have long found that more ideologically extreme candidates face an electoral penalty. There’s some evidence that that penalty is weakening but as Matt Yglesias documents, it’s not disappeared.

A 2018 paper by Andrew Hall and Daniel Thompson looked at US House elections between 2006 and 2014 and concluded that moderates performed better. The mechanism here is interesting: the study finds that more extreme candidates do drive turnout, but “extremists appear to activate the opposing party’s base more than their own.” In other words, they drive more counter-mobilization than mobilization.

A possible explanation is that the politically engaged are relying too heavily on introspection when thinking about the politically disengaged. The Knight Foundation just conducted a massive survey of “chronic nonvoters” and found, as many studies have before, that chronic nonvoters aren’t more liberal or conservative than voters in general — they were more mixed in their political beliefs, and simply less interested in politics. Nonvoters were, for instance, a bit more conservative on immigration than voters:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19775515/Screen_Shot_2020_03_07_at_10.13.01_AM.png) The 100 Million Project.

The 100 Million Project.They were muddled on healthcare:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19775525/Screen_Shot_2020_03_07_at_10.36.52_AM.png) The 100 Million Project.

The 100 Million Project.They were somewhat less likely to say the 2020 election is unusually consequential:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19775519/Screen_Shot_2020_03_07_at_10.11.52_AM.png) The 100 Million Project.

The 100 Million Project.They were somewhat less unfavorable towards Donald Trump:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19775523/Screen_Shot_2020_03_07_at_10.11.24_AM.png) The 100 Million Project.

The 100 Million Project.Importantly for those who believe nonvoters want a more transformational and disruptive agenda, they were somewhat less likely to say the country is on the wrong track:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19775542/Screen_Shot_2020_03_07_at_10.11.39_AM.png) The 100 Million Project.

The 100 Million Project.Bigger differences could be found in their political information habits. Nonvoters were a lot likelier to say they didn’t follow political news closely:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19775526/Screen_Shot_2020_03_07_at_10.40.39_AM.png) The 100 Million Project.

The 100 Million Project.And they were likelier to grow up in households that didn’t follow political news closely:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19775528/Screen_Shot_2020_03_07_at_10.41.06_AM.png) The 100 Million Project.

The 100 Million Project.One of the easiest and most common fallacies in politics is to imagine that one’s own political reactions are generalizable. But there’s no evidence that a more sharply ideological agenda and a more conflict-driven theory of politics will turn out nonvoters. That’s often what the most politically active voters find mobilizing, but the most politically engaged are, by definition, quite different than the least politically engaged, and so there’s no reason to believe that what the two groups want are the same.

The misperceptions here are likely compounded by Twitter, which has an outsized role in shaping how both media and political elites perceive politics, but misrepresents the electorate. A February Pew study found that Democrats on Twitter were significantly more conflict-oriented than Democrats off Twitter, and perhaps for that reason, Democrats on Twitter were significantly more likely to support Sanders or Elizabeth Warren over Biden than Democrats off Twitter. This held true even when looking at Americans who leaned Democratic but weren’t registered to vote.

This is not to say that Biden is likely to turn out scores of chronic nonvoters. I don’t think he is. But it helps explain why the turnout he did generate among normal Democrats wasn’t swamped by nonvoters activated by Sanders’ message.

2020 is a referendum on Trump, not on the Democratic agenda

In his new book Un-Trumping America, Pod Save America’s Dan Pfeiffer writes that “The biggest divide in the Democratic Party is not between left and center. It’s between those who believe once Trump is gone things will go back to normal, and those who believe that our democracy is under a threat that goes beyond Trump.”

The Democratic debates have, for obvious reasons, featured Democratic candidates arguing with each other. Differentiating from each other means going beyond their shared differences with Trump. At almost every debate, the various candidates say that it’s not enough to simply beat Trump — you need a bigger agenda, a more inspiring vision. “We’re trying to transform this country, not win an election, not just beat Trump,” Sanders told Rachel Maddow.

Biden is the closest thing to a candidate who disagrees. His tag line is that he’ll “beat Trump like a drum.” He routinely gets criticized by liberals for saying things like “history will treat this administration’s time as an aberration,” or “This is not the Republican Party.” His answers trade heavily on nostalgia for the Obama administration, which is to say, for the pre-Trump status quo. It’s basically as close to the Democrats’ 2018 congressional strategy as a presidential campaign can run.

This annoys leftists who think the Obama administration was characterized by neoliberal half-measures and liberal analysts who think, like Pfeiffer does, that Trump is symptom, not cause, of America’s political crisis. if you read my profile of Biden, you’ll know I side with the critics on this one. But most Democrats seem to agree with Biden. As CNN noted, “majorities of Democratic voters in every Super Tuesday state said they would prefer a nominee who can beat Trump over one with whom they agree on the issues.”

Biden’s has run almost as a generic Democrat, framing the election as a choice between Donald Trump and Barack Obama. As I’ve written before, I find this frustrating, as Obama is not on the ticket, but it has a certain political logic. The single scariest fact for Democrats in 2020 is that economic confidence is higher than it’s been since 2000:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19775567/Screen_Shot_2020_03_07_at_11.15.32_AM.png) Gallup

GallupLiberals can give you chapter and verse on how the economy is actually worse than it seems, and I think a lot of those arguments are correct. In particular, surveys that measure the strength of the economy may miss the pressures of the affordability crisis. Still, Democrats have to face the fact that there are a lot of voters who are happy with the economy and just don’t like Trump. Biden’s pitch to them, basically, is that he’ll remove Trump from office but not do anything drastic to alter economic trends. That may be a better strategy than much of the left believes.

Democrats have settled on two risky choices

Democrats have a difficult task in 2020. Trump is the incumbent amidst, for now, a growing economy. Presidents almost never lose under those conditions. Moreover, Trump has a significant advantage given the country’s electoral geography: it’s entirely possible the Democrat could once again win more votes and lose the electoral college.

And Democrats are not, in my view, playing it safe. The field has winnowed down to a 77-year-old icon of the Democratic establishment who has trouble expressing himself and a 78-year-old democratic socialist who just had a heart attack. And both of them are criss-crossing the country holding public events amidst the outbreak of a virus that’s particularly dangerous for older Americans. There were, in my view, a number of less risky choices in the Democratic field, but voters rejected them.

Of course, Trump is, himself, a risky choice for Republicans. Despite the strong economy, he has never broken 50 percent in polling averages. He lost the popular vote in 2016, led Republicans to electoral wipeout in 2018, and got himself impeached in 2019. His White House has been chaotic, he is more rhetorically reckless than Biden, and he is also a septuagenarian in middling physical health.

On Super Tuesday, Biden showed that a campaign that has been singularly uninspiring to the most engaged sliver of the electorate was able to turn out the most voters. Those of us who didn’t see it coming need to rethink our priors.

Author: Ezra Klein

Read More