We can’t solve our climate-change problems by having fewer babies.

In response to a Vox column of mine suggesting that the United States needed a pro–population growth agenda, many readers from across the political spectrum responded by raising fears about overpopulation.

Clearly, fear of overpopulation is widespread.

But the truth is that overpopulation in the United States is not even close to a serious problem. Even globally, overpopulation is an overstated problem.

It’s simplest to start with just the United States. How many people can the country support? Because I am an agricultural economist by profession, my bias is to first think about food. One simple question is how many people can the United States feed? Well, our net agricultural exports account for about 25 percent of the physical volume of agricultural production, which suggests that if we redirected those exports internally, the US could probably support approximately 25 percent more people. That’s assuming current technology and current diets and current land use.

In short, we could feed more than 400 million people, total, merely by consuming locally what we now export.

If you assume that a growing population induces more land to be shifted to food production (because farming becomes more profitable), that food imports can rise, and that agricultural innovation continues apace, it becomes clear that our land can physically support even more people than that — I estimate as much as double our current population. And given that agricultural yields are far lower in the developing world today than in the United States, thanks to the much lower level of technological advancement and managerial expertise in those countries, the truth is that the rest of the world has plenty of potential for increased food production: more than enough to feed itself and provide imports for a more populous United States. Merely tweaking foreign land use rules could unlock large gains in agricultural production.

I also approach this problem as a regional economist specializing in migration, so I also think of the American population issue through the lens of population density comparisons. Consider that the European Union has approximately 300 people per square mile, making it as dense as the ninth-densest US state (that is, similar to Pennsylvania or Florida). The continental United States on the whole has about 110 people per square mile (excluding Alaska, an outlier), making the US less than one-third as densely peopled as the EU. Yet the European Union, too, has roughly balanced or even slightly positive agricultural trade. That suggests that Europe, too, has no trouble feeding itself despite being three times as densely settled as the United States.

If the continental United States were as heavily settled as the EU, the US would have nearly a billion people living in it. Granted, the Western US is extremely dry and thus might not support an EU-density population. (Again, I assume we aren’t going to populate remote Alaska.) Nonetheless, if just the states east of the Mississippi had European-style population density, and the other states maintained current population, then the United States would still have more than 400 million people.

Every time I show Americans these calculations, they respond with surprise, but the truth is that getting European-style densities wouldn’t require technological change. It wouldn’t even require any non-voluntary lifestyle changes or new regulations: Simple deregulation of the housing industry would do the trick. Reducing parking requirements for new apartment buildings, removing height limits, altering restrictive lot sizes (namely lot minimums), and generally just allowing landowners to build freely on their property would greatly reduce the cost of living and boost population growth and density. It would prompt Americans to move to denser areas while also lowering housing prices and easing family budgets — which would itself increase fertility. (Recall that many American families wish they could afford more children.)

Population growth is the least influential part of the climate change calculation

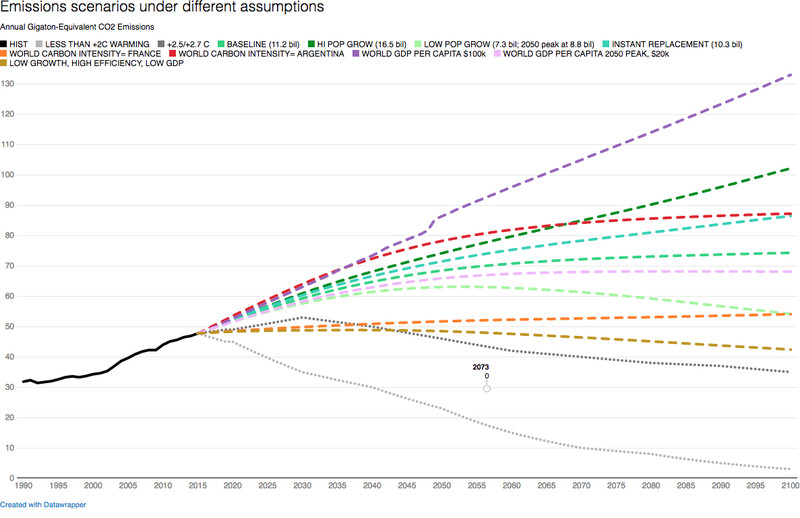

The concern with overpopulation, naturally, often dovetails with concerns about climate change. Won’t higher population devastate the environment? We can answer that question fairly easily, making use of forecasts of population, GDP per capita, and emissions intensity per dollar by country. We can come up with some scenarios and then compare them to estimates of emissions needed to keep global warming manageable.

Lyman Stone

Lyman StoneI show a daunting number of scenarios above, but they’re color-coded to make following them easier. The greenish lines show emissions under different population scenarios. The most steeply climbing line assumes only a modest decline in global fertility rates, while the lowest (green) scenario assumes a very rapid decline in total fertility rates — frankly, an unattainable decline.

The teal line assumes that fertility rates in every country go directly to replacement rate in 2016 (down for most poor countries, up for rich ones), and stay there. The central green line assumes fertility declines in the future following the historic trend. As you can see from these crude extrapolations, fertility rates do have substantial long-run effects on emissions.

But note those two gray lines. They’re important: They show where emissions need to go in order to prevent sharp rises in global temperatures. The paler of the two shows emissions required for less than 2 degree Celsius increase, broadly seen as the benchmark for a “serious” global warming solution. The darker gray line would get us down to a 2.5 to 2.7 degree increase, which is more or less what the Paris climate agreement committed participating countries to strive for. No amount of population control achieves those goals.

One challenge is that lower fertility leads to higher consumption and economic output

One complication is that fertility decline tends to increase GDP per capita, as families invest more in human capital for each child. What happens if GDP growth is much faster than in my baseline scenario? That sharply rising purple line shows emissions if we retain baseline fertility but global GDP per capita rises to $100,000 real dollars. (It is under $12,000 today.) The much lower pink line shows what happens if we retain current fertility but global GDP per capita peaks in 2050 at about $20,000, then declines. Emissions are much lower, but they’re still far above the levels necessary to prevent extreme warming.

Finally, the red and orange lines show different assumptions about technology and society. The red line assumes that the amount of CO2 it takes to produce $1 of GDP declines much slower than it has in the past 25 years. The orange line assumes it declines substantially faster. Achieving either scenario requires a global economy that is substantially less dependent on fossil fuels than it is today in either case, but reaching the most optimistic scenario requires a near-total elimination of fossil fuel power generation on developed countries (as France has done, with its commitment to nuclear power).

Either scenario is technologically possible, though we would need big breakthroughs in cost-effectiveness of alternative energy for the best-case outcomes. But compared to the “cost” involved, these tech and social measures have the biggest bang.

But unfortunately, even if we combine lower fertility, more efficient technology, and lower economic growth (the brown line), by the 2030s we are once again overshooting necessary emissions. In other words, this entire exercise is hopeless within current technological constraints. The only hope for the climate is a quantum-leap breakthrough in carbon efficiency — beyond what we observe in even very carbon-efficient economies. Fertility on its own won’t make a serious dent.

And it gets worse: Fertility declines may offset themselves even when couples have zero children. An American couple that forgoes a child might take an extra vacation, say, a road trip across Peru — burning extra fossil fuel for airfares and extra driving. The couple’s plane ticket alone to Peru would produce between 3 and 7 metric-ton equivalents of CO2. Add in the couple’s double consumption of housing (their home is vacant while they travel), their increase in driving (it’s a road trip), their increase in eating and other consumption (it’s vacation, after all), and that single vacation has about the same carbon impact as a baby in its first year (some 10 tons of carbon, let’s estimate).

Because of this higher-intensity consumption by childless couples, while lower fertility could reduce long-run emissions, it probably has no net impact on short-run emissions — or even increases them. And short-run emissions have the largest impact on future temperatures (because there is a time delay between carbon emissions and climate impact).

Concerns about population growth are especially irrelevant in low-growth countries like the US

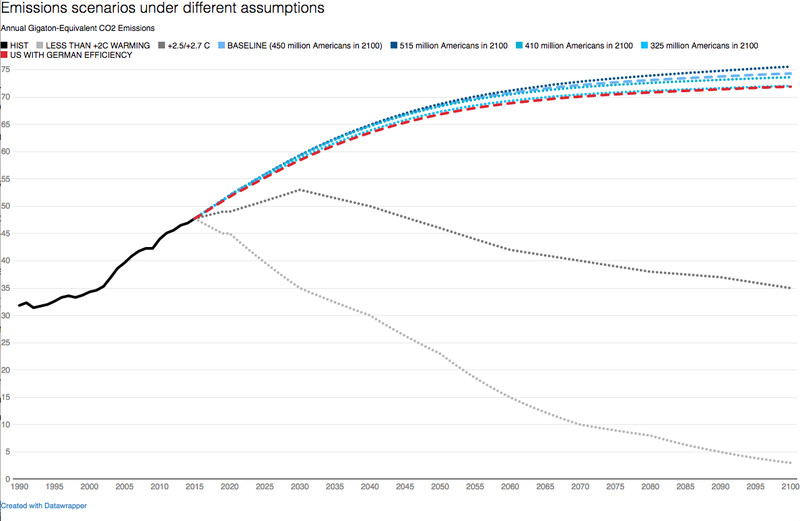

But this is all moot when considering the United States! The US has lower carbon intensity per dollar of GDP than average for the world, and US population growth is an extremely small component of global emissions forecasts. And since US population and GDP growth are already extremely low in comparison to the rest of the world, marginally raising fertility will have an infinitesimally small impact on the growth path of carbon emissions. Virtually the entire determinative calculation for future carbon emissions can be summed up in the pace of shifts away from fossil fuels in the largest economies, and the population and economic growth trajectories in developing countries.

Lyman Stone

Lyman StoneAs you can see, even if US population stopped growing at around 325 million people in 2017 and flatlined out, it would produce at best a marginal change in global emissions. Plus, accomplishing that trend would require draconian anti-fertility policies and extremely strict immigration laws. On the other hand, even if US population rises over 500 million people, the impact on the world is barely noticeable. Meanwhile, lowering US carbon intensity by about a third, to around the level of manufacturing-superpower Germany today, has a bigger effect than preventing 100 million Americans from existing.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Bettmann Archive/Getty ImagesNow, obviously, we should provide the resources for women to take ownership of their fertility: We should want to reduce undesired conceptions and increase desired conceptions. We should facilitate the kind of human development that tends to reduce desired fertility from the four- to seven-child range to the two- to four-child range as well. But we should do these things because it is morally good to empower individual decision-making, not because we can save the climate through Malthusian reductions.

There is only one way to effectively prevent, alleviate, or reverse dangerous climate change: technological, geographic, and social advancement. Population has little to do with it — especially not in the US.

Lyman Stone, a Vox columnist, is a regional population economics researcher who blogs at In a State of Migration. He is also an agricultural economist at USDA. Find him on Twitter @lymanstoneky.

The Big Idea is Vox’s home for smart discussion of the most important issues and ideas in politics, science, and culture — typically by outside contributors. If you have an idea for a piece, pitch us at [email protected].

Read More

https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/community_logos/52517/voxv.png