Da 5 Bloods, like all his movies, doesn’t let anyone off the hook.

Spike Lee does not let you simply watch his movies. When Lee makes a film, he isn’t thinking of you as another passive body in a seat, munching on popcorn, being entertained by a story he’s cooked up. Oh, he’ll entertain you, no doubt about that. But when you watch a Spike Lee joint, you’re not allowed the luxury of objectivity. Like it or not, you become part of the movie.

And it’s not just his pointedly apposite subject matter that sucks you in. Lee’s films don’t scream, “Now, more than ever!” The word “urgent” is a critical bromide, but Lee lives outside the cliché. He is, in content and in form, a true filmmaker of urgency.

Plenty of filmmakers aspire to be “provocative,” to make the audience feel uncomfortable and exhilarated all at once. (For a recent example, consider The Hunt, a movie which, if it were an actual person, would have smugly added “provocateur” to its Twitter bio as soon as someone got mad about it.) But Lee has been landing jabs and uppercuts and sometimes even haymakers on his targets for decades. He’s a provocateur who doesn’t need to tell you how provocative he — or, most importantly, his work — is.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20030185/D5B_Unit_06807RC.jpg) David Lee/Netflix

David Lee/NetflixLee, who turned 63 in March, exploded onto the scene while he was still in graduate school. His 1983 master’s thesis film Joe’s Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads was the first student film ever to play in Lincoln Center’s prestigious New Directors/New Films festival. It went on to win a Student Academy Award.

His second feature film, 1989’s Do the Right Thing, was a bona fide sensation, netting the director an Oscar nomination and a berth in the canon of great American film directors. It’s arguably the most indispensable movie about race and police violence from an American director — certainly among the top five — and it launched a career that’s littered with peaks and valleys, messes and masterpieces, and always indubitably the work of Spike Lee.

His latest and 24th feature film is Da 5 Bloods, which follows on the heels of his first competitive Oscar win for 2018’s BlacKkKlansman’s adapted screenplay. Like that film, Da 5 Bloods leans into genre trappings (this time, some cross between a war movie and a buddy comedy), but with a bent that’s all Lee. On its surface, it’s a tale of four black Vietnam vets who return to the country decades after their tours of duty in search of gold and their fallen buddy’s remains. But Da 5 Bloods is also a fiery union of his fiercest themes — race, trauma, and power’s corrupting effect — with a particular interest in when past history and present reality start rhyming.

Starring Norm Lewis, Clarke Peters, Isiah Whitlock Jr., Jonathan Majors, and a magnificent Delroy Lindo, Da 5 Bloods takes on myriad issues (no one would ever accuse Spike Lee of aiming too low), starting with the Vietnam veterans, a sharply disproportionate number of whom are black and who were left to live with the remnants of a pointless war long past when the rest of us had moved on. They went to war, which was hell. They came back to a hell of a different kind.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20030187/D5B_Unit_03079RC.jpg) David Lee/Netflix

David Lee/NetflixLee weaves that strand of history into the broader canvas of the 1960s and ’70s, from the civil rights movement to the moon landing. Then he extends it into today, all the way to the Black Lives Matter movement.

But Lee and his BlacKkKlansman co-writer Kevin Willmott (working from an initial draft by Danny Bilson and Paul De Meo) never make the narrative lines too straight. Lindo gives a staggering performance as Paul, whose traumas have turned him into a MAGA-hat-sporting spout of paranoia, to the discomfort of both his friends and his son, David (Majors), a Morehouse alum who comes looking for his father after he returns to Vietnam. That narrative choice alone means that Da 5 Bloods, while political to the bone, refuses to be stuffed into partisan pigeonholes. What it means to be black in America does not fit into tidy fables.

In Da 5 Bloods, Lee brings back many of his signature filmmaking moves that rope the audience into the story

Watching Da 5 Bloods, I found myself frequently pinned to my couch, laughing at the acerbic and sometimes goofball humor, at least when I wasn’t biting my fist. It’s a bloody, screwy, incendiary piece of work, and I loved it, especially when it goes flying off the rails near the end.

It’s also propulsively immersive; I half expected someone to stick a fist through the screen and grab me. In this way, Da 5 Bloods is like many of Lee’s films — willing to break the rules of fiction and nonfiction, of the separation between audience and movie with which moviegoers have been trained to watch films.

It’s startling, for instance, when a character on screen suddenly looks at you, addresses you, starts telling you what they’re thinking. The screen is a fourth wall, a fiction that makes us think we’re looking through a window into an alternate reality wherein they don’t know we’re here — a one-way mirror, with us hidden from view. But Spike Lee likes to have his characters look back and directly into the camera, to startle us with the realization that they perceive us as part of their world on screen. They’re sharing something with us, sometimes by talking to us and sometimes just by casting a knowing glance, with examples ranging from Samuel L. Jackson’s roving one-man Greek chorus in Chi-Raq (2015) to youthful Troy giving us a knowing glance from the back seat of a car in Crooklyn (1994). In Da 2 Bloods, Lee again includes that sense of offscreen recognition in one particularly electrifying scene that ends with an upraised fist of power and protest.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20030195/crooklyn.jpg) Courtesy of Universal Pictures

Courtesy of Universal PicturesLee also refuses to submit to a barrier between fact and fiction. Frequently, and especially in his more recent work (including Da 5 Bloods), he splices together montages of archival footage, news reports and speeches and moments we previously experienced on screens, reminding us that what we saw was both real and framed, shot for our consumption. Over time, history gets reduced to iconic images from newsreels and grainy pictures. By putting them in the context of his movies, Lee revives them, putting his films into a context that’s both cinematic and far bigger than cinema alone.

And it’s not just news footage that’s part of this; cinema is revised in his hands, as well. BlacKkKlansman ended, startlingly, with images of white supremacists at 2017’s “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, but it started with images from the highest-grossing film of all time, 1939’s famously racist Gone With the Wind.

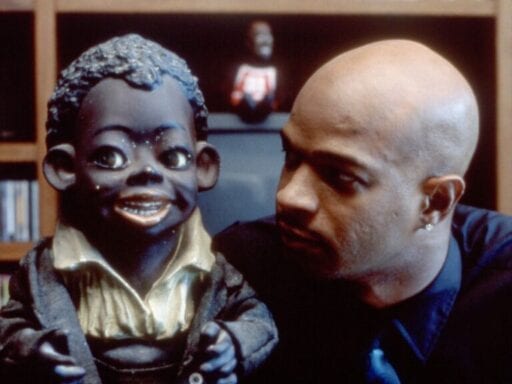

Sometimes his references to cinema are cheeky. In his 2000 film Bamboozled, he adds a tiny scene of Malcolm X telling a crowd they’ve been “bamboozled,” except it’s not Malcolm; it’s Denzel Washington playing him in Lee’s own 1992 film. But he alludes to cinema more powerfully at the end of Bamboozled, when a black TV executive, fed up with his white boss’s propensity to cancel TV shows with positive depictions of black characters, pitches an outrageous show featuring black minstrels performing in blackface. After using this uproarious, incredibly uncomfortable setup to probe the heart of racism in the American entertainment industry, and the guilt we all share, Bamboozled ends with a lengthy clip montage of minstrelsy stereotypes, mostly drawn from early animation and Hollywood’s Golden Age. This has been going on forever, Lee says, and the results were not restricted to what you saw on screen.

In Da 5 Bloods, Lee does this partly by playing with the image itself, borrowing from movies like Apocalypse Now to evoke a war that many of us have only experienced through a movie screen. The aspect ratio of the film changes depending on where we are in the characters’ mental space and existential journey, sliding from widescreen to narrow 16mm to full frame, with the image becoming more grainy in “older” scenes even though the actors aren’t de-aged at all. Remember, Lee says: This is only a movie. But much of what we know of real life is through a movie. The two have collapsed into one.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20030201/DA_5_BLOODS_Vertical_Teaser_EN_US.jpg) Courtesy of Netflix

Courtesy of NetflixSo much of what happens in Da 5 Bloods is emblematic of how Lee insists you engage with the film as a mindful participant, not just as a passive observer. Most anyone would have to be purposefully obtuse not to recognize themselves somewhere in Da 5 Bloods, and thus in the history it recounts, in the same way that BlacKkKlansman refuses to let the audience think that its events happened in the “past.” Characters talk to us. Familiar figures from history appear on screen. The fictional characters blur into reality. And it feels very, very real.

Which is what Lee has always been after. There’s an exuberant, angry sagacity to a Spike Lee joint, which is why even the messier ones, or the ones that leave critics arguing, are always worth seeing. His films live in the same world as the audience. They collapse the boundaries between audience and image. When you watch a man burn a cork and blacken his face in Bamboozled, you’re seeing an actor play a part, but you’re also really watching a black man put on blackface to perform in a movie. When you’re listening to four old black men talk about being Americans, they’re actors playing characters, but they’re telling the truth, too. The characters’ history is the actors’ and the viewers’ history, too. When Lee dedicated Do the Right Thing to six victims of police violence in 1989, it wasn’t a gesture: It was a prophecy. He’s been watching closely. And he won’t let us off the hook.

Da 5 Bloods premieres on Netflix on June 12.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Alissa Wilkinson

Read More