This may, just may, have influenced Trump’s decision to nominate him to the Supreme Court.

President Donald Trump has picked a Supreme Court nominee, Brett Kavanaugh, who doesn’t think presidents should have to spend their time on pesky criminal investigations.

Perhaps not coincidentally, President Trump has been spending a lot of time dealing with a pesky criminal investigation.

Kavanaugh wrote in an article for the Minnesota Law Review from 2009 that Congress should pass a law “exempting a President—while in office—from criminal prosecution and investigation, including from questioning by criminal prosecutors or defense counsel.”

“I believe that the President should be excused from some of the burdens of ordinary citizenship while serving in office,” Kavanaugh wrote. “We should not burden a sitting President with civil suits, criminal investigations, or criminal prosecutions.” Furthermore, Kavanaugh opined that the “indictment and trial of a sitting President” would “cripple the federal government.”

Now, this is in the context of calling for Congress to change existing law — not for the Supreme Court to interpret it differently. However, these beliefs and opinions could well influence how Kavanaugh would rule on the major topics related to civil or criminal investigations that do end up reaching the Supreme Court.

And these are topics of enormous importance to Trump, who’s facing not just the Mueller probe over Russian interference with the 2016 election, but a civil suit over his foundation and a defamation suit from Summer Zervos, who has said Trump sexually assaulted her.

The Mueller probe has captured most of Trump’s attention, and he has endlessly complained about it. So no doubt he was thrilled to learn that Kavanaugh believed that similar investigations tend to be burdens on the presidency. Indeed, CNN’s Jim Acosta reported that the Trump team reviewed these comments by Kavanaugh before choosing him.

Trump SCOTUS team has looked at Kavanaugh’s past comments on indicting a sitting president, we’ve confirmed. In 2009, Kavanaugh wrote: “The indictment and trial of a sitting President, moreover, would cripple the federal government…” https://t.co/rDHJs5RiUY

— Jim Acosta (@Acosta) July 9, 2018

“I’m a little sort of stunned at the way this has all played out,” Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ) said on MSNBC Monday night. “If you look at the entire list of 20 or so people that he had, the one person the president could find on that list that would be most assured to rule in his favor should many of the things you’re describing come before the Supreme Court, is this guy.”

What Kavanaugh wrote about the president, criminal investigations, and civil suits

From 2001 to 2006, Kavanaugh worked in George W. Bush’s White House, first in the White House Counsel’s office and then as White House Staff Secretary. In 2006, he was confirmed to the US court of appeals for the DC circuit, and then in 2009, he wrote an article that would be published in the Minnesota Law Review.

The article addressed several issues related to the presidency and separation of powers, but the most relevant section comes right after the introduction, and focuses on criminal and civil investigations of sitting US presidents:

Kavanaugh opens here by describing his work for President Bush and how he learned to appreciate “how complex and difficult that job is,” and continues (emphasis added):

I believe it vital that the President be able to focus on his never-ending tasks with as few distractions as possible. The country wants the President to be “one of us” who bears the same responsibilities of citizenship that all share. But I believe that the President should be excused from some of the burdens of ordinary citizenship while serving in office.

He calls on Congress to consider passing a law that would relieve some of those burdens — and expresses his doubt that investigations of a sitting president can rise above politics.

In particular, Congress might consider a law exempting a President—while in office—from criminal prosecution and investigation, including from questioning by criminal prosecutors or defense counsel. Criminal investigations targeted at or revolving around a President are inevitably politicized by both their supporters and critics.

As I have written before, “no Attorney General or special counsel will have the necessary credibility to avoid the inevitable charges that he is politically motivated—whether in favor of the President or against him, depending on the individual leading the investigation and its results.”

Kavanaugh goes on to bemoan the consequences if the sitting president were to be indicted.

The indictment and trial of a sitting President, moreover, would cripple the federal government, rendering it unable to function with credibility in either the international or domestic arenas. Such an outcome would ill serve the public interest, especially in times of financial or national security crisis.

This is a genuinely unsettled legal question — Justice Department opinions have tended to state that a sitting president can’t be indicted, but some experts have argued otherwise. The question has never been tested in the courts, but it was revived last year with the scandal over Trump, Russia, and possible obstruction of justice. Mueller seems unlikely to defy Justice Department policy with a legally questionable indictment of Trump, but if that were to take place, the matter would surely be decided by the Supreme Court.

Kavanaugh continues:

Even the lesser burdens of a criminal investigation—including preparing for questioning by criminal investigators—are time-consuming and distracting. Like civil suits, criminal investigations take the President’s focus away from his or her responsibilities to the people. And a President who is concerned about an ongoing criminal investigation is almost inevitably going to do a worse job as President.

This will also likely resonate with Trump, who’s spent an enormous amount of time on the Mueller probe and has been plagued by other lawsuits as well. Indeed, one current topic of discussion is whether Trump should have to sit for “questioning” by Mueller. If Trump were to refuse to be questioned, Mueller could subpoena him, and that battle would likely rise to the Supreme Court.

Kavanaugh concludes by briefly trying to address two possible critiques of his arguments. First, he says that the president could always be prosecuted after he leaves office. Second, he says that if the president were to do anything really bad, Congress has the impeachment process.

One might raise at least two important critiques of these ideas. The first is that no one is above the law in our system of government. I strongly agree with that principle. But it is not ultimately a persuasive criticism of these suggestions. The point is not to put the President above the law or to eliminate checks on the President, but simply to defer litigation and investigations until the President is out of office.

A second possible concern is that the country needs a check against a bad-behaving or law-breaking President. But the Constitution already provides that check. If the President does something dastardly, the impeachment process is available. No single prosecutor, judge, or jury should be able to accomplish what the Constitution assigns to the Congress. Moreover, an impeached and removed President is still subject to criminal prosecution afterwards.

Yet Kavanaugh doesn’t address the question of what happens when it’s not clear and disputed whether or not the president has done “something dastardly” — such as, colluding with Russia to intervene in the 2016 election, or obstructing justice. It appears he would be happy to leave that up to Congress to determine, without any investigation from the executive branch.

He concludes the section:

In short, the Constitution establishes a clear mechanism to deter executive malfeasance; we should not burden a sitting President with civil suits, criminal investigations, or criminal prosecutions. The President’s job is difficult enough as is. And the country loses when the President’s focus is distracted by the burdens of civil litigation or criminal investigation and possible prosecution.

Kavanaugh went on a journey to get here

What’s particularly odd about this coming from Kavanaugh is the fact that, in the 1990s, he worked on independent counsel Ken Starr’s extremely zealous team of prosecutors pursing what they believed to be wrongdoing from President Bill Clinton.

The independent counsel investigation into Clinton began with a land deal in Arkansas and eventually ended with a report recommending his impeachment for lying under oath and obstructing justice over his affair with Monica Lewinsky.

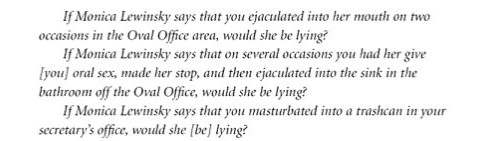

According to Ken Gormley’s book The Death of American Virtue, Kavanaugh was a particularly committed member of the team. At one point, he wrote a memo to Starr that included the following:

“After reflecting this evening, I am strongly opposed to giving the President any “break”… unless before his questioning on Monday, he either i) resigns or ii) confesses perjury and issues a public apology to you [Starr]. I have tried hard to bend over backwards and be fair to him… In the end, I am convinced that there really are [no reasonable defenses]. The idea of going easy on him at the questioning is abhorrent to me…

“[T]he President has disgraced his Office, the legal system, and the American people by having sex with a 22-year-old intern and turning her life into a shambles—callous and disgusting behavior that has somehow gotten lost in the shuffle. He has committed perjury (at least) in the Jones case… He has tried to disgrace [Ken Starr] and this Office with a sustained propaganda campaign that would make Nixon blush.”

Per Gormley, Kavanaugh’s memo went on to propose asking President Clinton questions such as the following:

Kavanaugh seems to have completely changed his mind on the topic after later working for a president of his own political party. Indeed, he obliquely admits this in the 2009 Minnesota Law Review Article, writing:

This is not something I necessarily thought in the 1980s or 1990s. Like many Americans at that time, I believed that the President should be required to shoulder the same obligations that we all carry. But in retrospect, that seems a mistake.

Looking back to the late 1990s, for example, the nation certainly would have been better off if President Clinton could have focused on Osama bin Laden without being distracted by the Paula Jones sexual harassment case and its criminal investigation offshoots. To be sure, one can correctly say that President Clinton brought that ordeal on himself, by his answers during his deposition in the Jones case if nothing else.

Kavanaugh seems to be suggesting that his years on the Starr investigation actually made the country worse off and perhaps even helped prevent President Clinton from catching Osama bin Laden.

Luckily for Kavanaugh, however, the opinion about presidential investigations that he ended up at nearly a decade ago has likely turned out to be one that President Trump finds quite congenial.

Read More

https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/community_logos/52517/voxv.png