Celebrate Harry Potter’s 20th anniversary by rereading Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, and become 9 years old again.

When I was 9 years old, the greatest day of the school year was the day of the Scholastic Book Fair.

Scholastic would set up shop in the school library, piling stack after stack of shiny new books on the tables. They gleamed against the library’s familiar collection of shabby older books, and I would wade into the feast and glut myself.

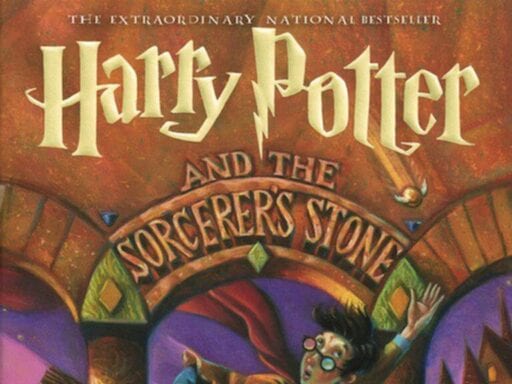

Mostly I went for the paperbacks; I had a book-a-day habit, and hardcovers were a rare treat. But when I first saw the purple and gold hardcover of J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, spangled with stars and looking weighty and solemn and magical, I couldn’t resist picking it up.

Mr. and Mrs. Dursley, of number four, Privet Drive, were proud to say that they were perfectly normal, thank you very much.

“Mom,” I said, “can I get this one? Please?”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6859463/IMG_0765.JPG)

It’s hard to remember Harry Potter before the franchise became a phenomenon

In 2016, when Scholastic released the script book for Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, its publication was accompanied by all the theatricality we’ve come to associate with Harry Potter releases: midnight launch parties, embargoes, and a furious black market for spoilers. It’s easy to forget, in the face of all the hoopla, that when Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone came out 20 years ago, it was just another book on the Scholastic Book Fair tables.

Sure, even then the book had high production values. Scholastic had shelled out $105,000 for American rights to the title — about 10 times the average — and the publisher wanted to recoup some of its costs. While the book’s British sales had been healthy, there was no indication at that stage that this particular book would become a beloved international bestseller.

But Scholastic had high hopes. So it invested in the production design, which including an eye-catching and soon-to-be-iconic cover. Rowling’s editors pushed her to let them alter the original title, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, by taking out “philosopher” to make the book more appealing to children. (Scholastic actually wanted to go with Harry Potter and the School of Magic; Rowling was the one who came up with “sorcerer’s stone.”)

The company developed a reasonably aggressive marketing campaign — no midnight release parties, just standard bookselling tricks like paying for the book to be displayed on the front tables at Barnes & Noble.

Still, this was nothing out of the ordinary. It was a budget on the high end of normal.

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone was just a book. A normal book with all the other normal books at the Scholastic Book Fair.

And then, of course, magic happened, and the book became a phenomenon.

The best part of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone is only halfway magical

The Harry Potter books are a mishmash of a few different genres. The later books feature a lot of epic fantasy/hero’s journey stuff and coming-of-age stuff, but all of that’s mostly gestured at in Sorcerer’s Stone. In some places — most notably Harry’s climactic confrontation with dull, stammering Professor Quirrell and a Voldemort who has not yet managed to acquire a personality — it’s downright weak.

But what works in this first book really works. And that’s the puzzle box mystery, the world building, and, most of all, the British boarding school tropes.

Rowling loves to misdirect, to hide her villains in plain sight and distract you with innocent red herrings. By the end of the series we were all wise to her tricks, but in Sorcerer’s Stone it was downright shocking to learn that, no, the sinister potions instructor who’s always swooping around like a bat and saying menacing things is not, in fact, the villain. The villain is that random guy in the background with the funny hat.

And then, of course, there’s the enormous, expansive reality of Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry and all the rest of the wizarding world. Most of it doesn’t make all that much sense — never try to make the math of the Harry Potter books work, you will get nothing out of it but a headache — but who needs sense when you have scope? It all feels real.

Rowling has a knack for crafting exact, specific details that make a world feel solid and lived-in. The witch Harry passes in Diagon Alley who’s complaining about the price of dragon liver, Ollivander measuring the space between Harry’s nostrils to fit him for a wand, the cart full of magical candies on the Hogwarts Express: It all comes together to create the sense of a vast, breathing world with its own rigorous rules and systems, one that keeps on existing when Harry’s not looking. It’s teeming with life, and it’s enchanting.

But what really brings this magical world to life is the fact that it exists within a British boarding school novel. As literary critic David Steege (among others) has pointed out, the Harry Potter books draw on the long tradition of “public school stories” that reached their peak in 1857 with Tom Brown’s School Days. These types of tales all concern wealthy bourgeois children having joyous school day adventures at various elite British boarding schools. They’re ubiquitous in the UK, and they come with all sorts of codified tropes.

As outlined in 1941 by one Edward C. Mack (and quoted by Steege), such tropes are as follows:

A boy enters school in some fear and trepidation, but usually with ambitions and schemes; suffers mildly or severely at first from loneliness, the exactions of fag-masters, the discipline of masters, and the regimentation of games; then makes a few friends and leads for a year or so a joyful, irresponsible and sometimes rebellious life; eventually learns duty, self-reliance, responsibility, and loyalty as a prefect, qualities usually used to put down bullying or overemphasis on athletic prowess; and finally leaves school, with regret, for the wider world, stamped with the seal of the institution which he has left and devoted to its welfare.

This is, more or less, exactly what happens to Harry, who enters Hogwarts simultaneously overjoyed to escape the Dursleys and terrified that he’ll be the worst in his class and have to wrestle a troll to find out what house he’s in. He makes friends for the first time in his life, and overcomes Draco Malfoy’s needling and Snape’s bullying to become popular with the rest of his classmates. He becomes a sports star. And he uses his newfound popularity and wisdom to help Neville Longbottom learn to stand up to bullies. It’s all very Tom Brown with magic wands.

The familiar tropes of the public school story genre — first there shall be school chums, then there shall be sports — are part of what makes Harry Potter’s magic feel so real and lived-in. The spell casting and spectacle are folded into this very mundane, bourgeois system whose every beat is instantly recognizable. It’s the same trick that more recent fantasy books like The Magicians use to ground their magic in something ordinary and everyday — it’s just that Harry Potter’s British boarding school story is more old-fashioned and mannered than The Magicians’ American college story.

And The Sorcerer’s Stone’s public school story tropes are its most compelling elements. Voldemort is just a vague outline of a cartoon villain at this point — his pureblood obsession isn’t even mentioned — and it’s hard to care too much about whether his evil plan gets foiled. But boy howdy do I care whether Harry wins the House Cup. I care about his blossoming friendship with Ron and Hermione. And I care about sneering, preening Draco Malfoy, the book’s true antagonist, whose rivalry with Harry is really what gives Sorcerer’s Stone its tension and forward drive.

In the later Harry Potter books, as Voldemort and his agenda grow more developed, Quidditch matches and House points will come to seem petty. But in this first volume, they’re the most important things in the world.

The Harry Potter books grow up as they progress, but Sorcerer’s Stone captures a specific feeling of childhood discovery

One of the greatest gifts of growing up with Harry Potter is that the books really did grow up with me. They got darker and harsher, with more ambiguity, as I got older and more equipped to handle those ideas. By the time Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows came out, and Harry and his friends left school for the first time to head out into the dangers of the world, I was in college, preparing to leave school myself.

But to this day, opening Sorcerer’s Stone sends me rocketing back to my 9-year-old self, to the time when my whole world was composed of school and my parents’ house. The book reminds me of what it felt like to enter this enormous, expansive, enchanting world for the first time, a world of wonder and whimsy where everything that really mattered happened within the walls of your school.

That feeling is peculiar to the books that imprint themselves on you at a very young age, and what’s astonishing about Harry Potter is that it was able to be that kind of book for so many people all at once. That’s what makes it magic.

Author: Constance Grady